Much of Britain now probably has sufficient soil moisture to see the combinable crops to harvest, especially oilseed rape and barley. We are projecting crop sizes of 7.1 million tonnes (mT) for barley (1.2 million less than 2020); 15.1 mT of wheat, approximately 50% rise on last year; 1.1 mT for OSR, 100,000 tonnes more than last year and about 100,000 tonnes more oats at 1.1 mT. Overall, including ‘other cereals’, we are anticipating 26.7 million tonnes, up from 22.8 mT last year. The figures are based on our expected crop areas and average crop yields 2014 to 2019. This represents no records in either direction. Whilst the crops areas appear relatively ‘typical’ we note there are still a lot of farms whose rotations are not back to what the management would have hoped for.

Old crop wheat prices have fallen £10 this month, slightly less than last month’s fall. Old crop and new crop always come together so when new crop harvest starts, they are the same. The fall is of little significance as so little is left. With such a large price spread between old crop and new crop, few farmers have held on to grain. New crop wheat values have fallen a Pound or so over the month, but have remained in a tight price range (£9.00 per tonne) since early April.

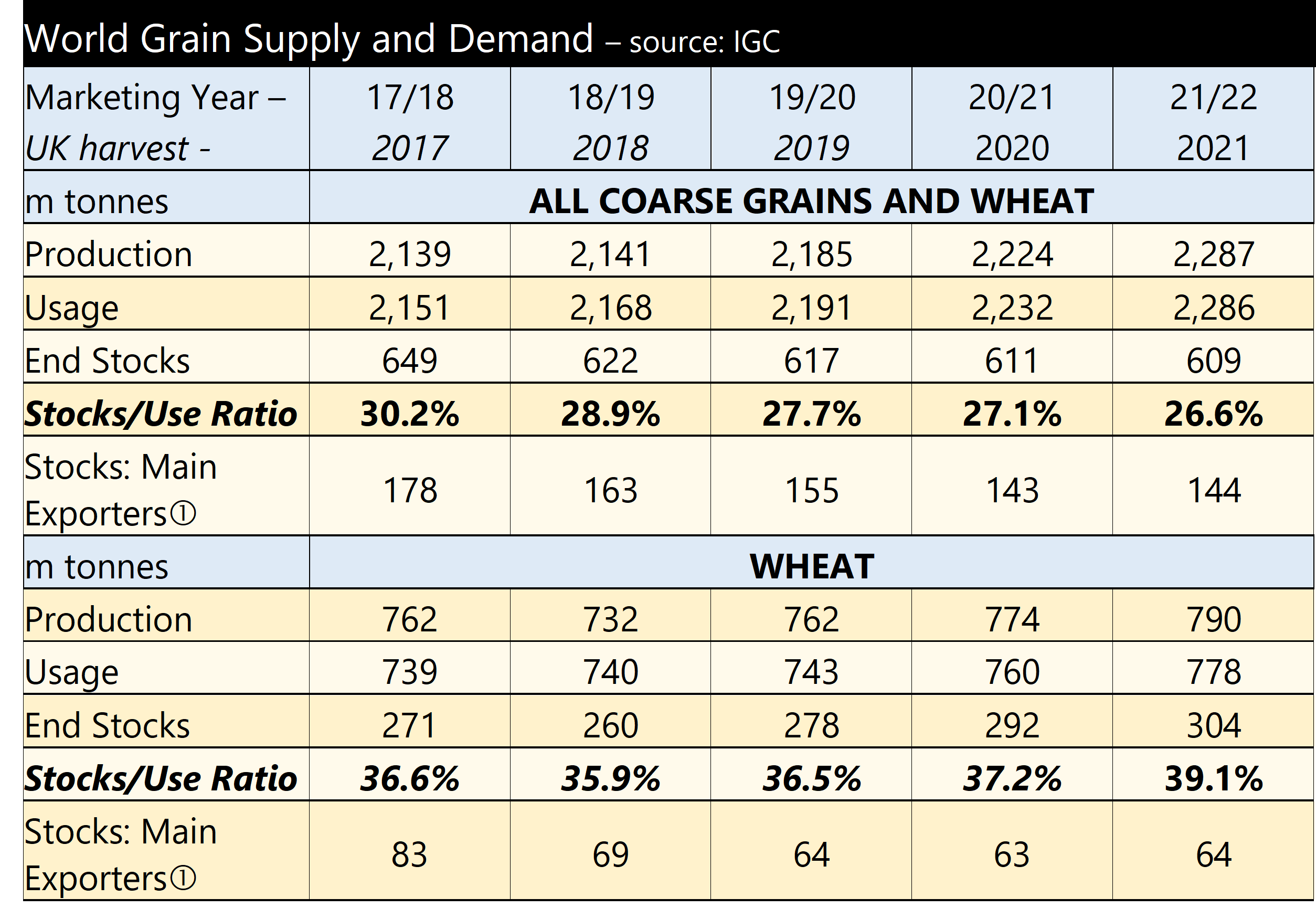

Across Europe, crop walkers have been reporting good yields pretty much everywhere. The French for example estimate over 80% of their crop is in good/excellent condition, this compared with 56% last year. Further afield, there is some concern that American crops are rather dry, but nobody is panicking yet.

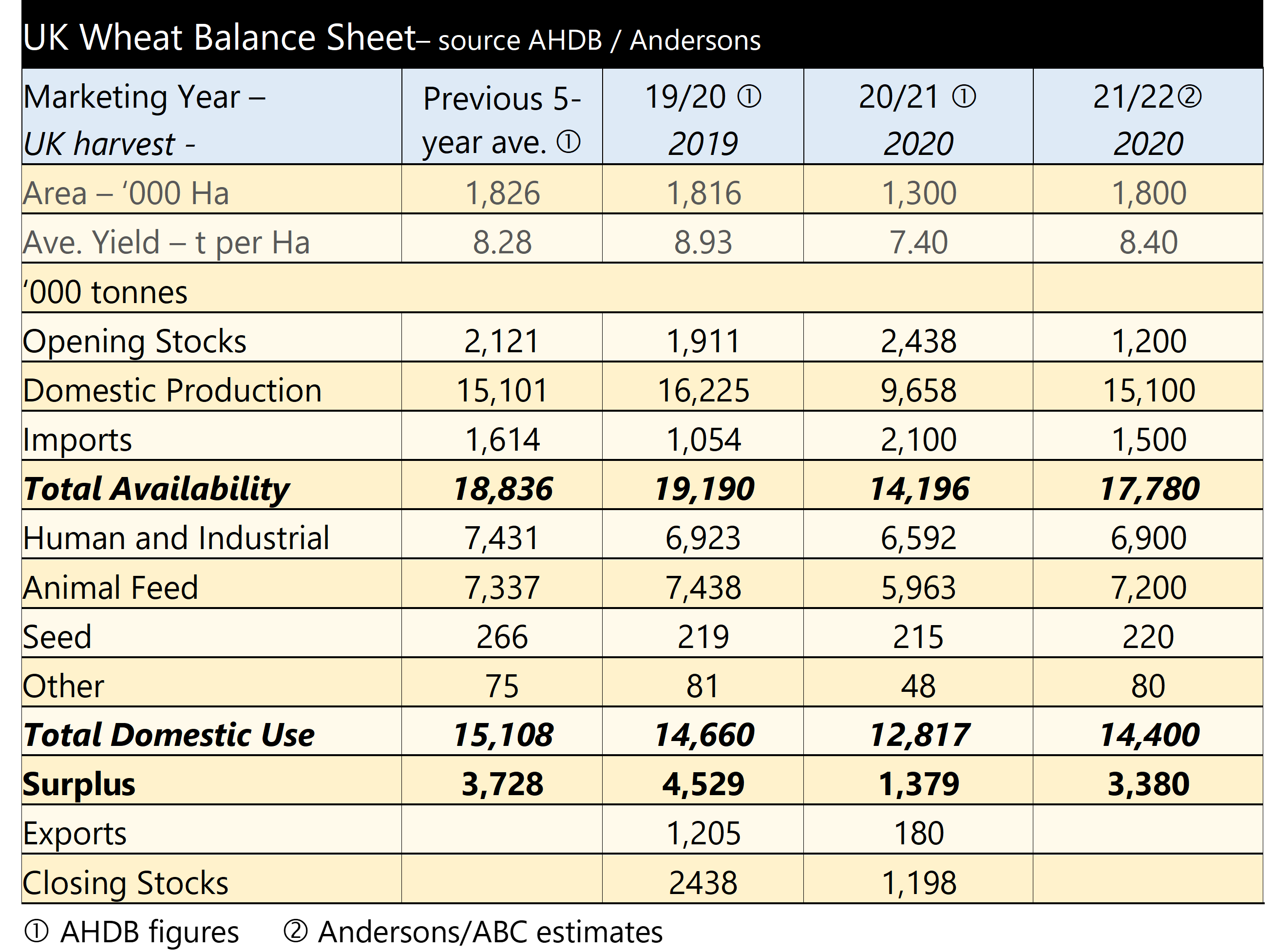

In the table below, we have updated previous years’ data with the AHDB estimates and our own thoughts and calculations for the 2021 harvest and its subsequent marketing year. We think that the UK will revert back to being a net exporter of wheat, having imported more than we exported last year. Export Parity (i.e. the price grain needs to be to be sold out of the country) tends to be lower than import parity (the price it has to be to stop imports from coming in from elsewhere).

The barley market is currently quiet, as the buyers are waiting to see what the new crop brings. UK barley is too dear compared with that from other locations to attract exports. It is also too close to wheat price for most feed mills.

The UK OSR crop is looking rather well as it starts ripening. This will be difficult to see for so many growers who decided not to grow it this year. One has to ponder how many growers will return to OSR this autumn for next year? We expect a rise in cropped area. Prices have shot up in the last month from already high levels. Normally we would expect oilseed rape to sit at about 2 to 2.2 times the value of feed wheat. We are currently between 2.5 and 3 times, depending on date of movement, making the comparative gross margin of OSR quite attractive. UK OSR is also trading at a premium over Paris rapeseed prices. This is because we have imported so much (over half a million tonnes) this season. This is mostly from beyond the EU. For those planning next year’s rotation, remember price relationships will be quite different by the time they are sold.