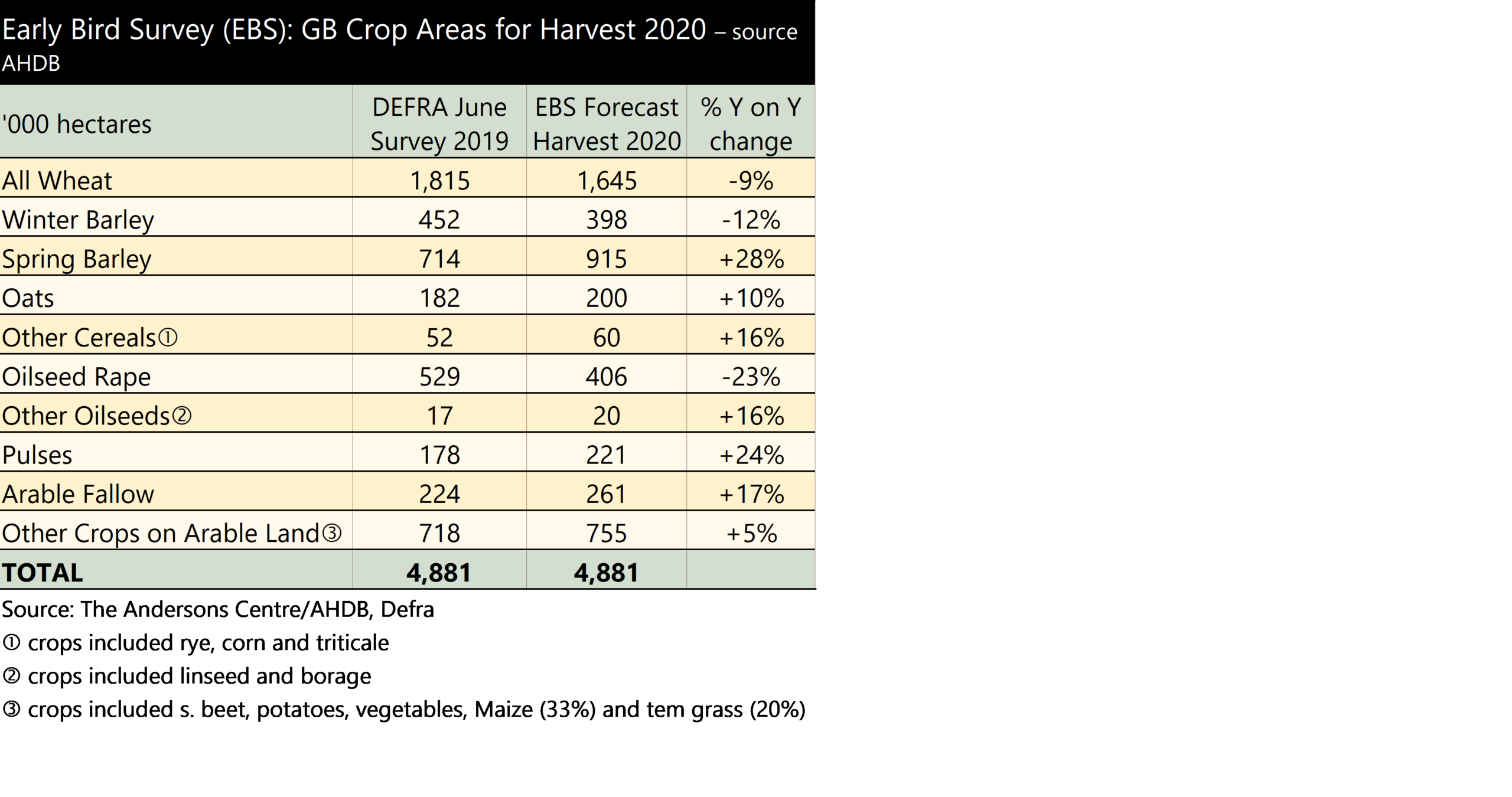

The AHDB’s Early Bird Survey of cropping and planting intentions for harvest 2020 was repeated in Mid-February. It shows a significant drop in winter cereals area, even more than in November (when it was first undertaken). For example, the winter wheat area is forecast to fall by 27%.

The table below shows a summary of the Early Bird results. Changes in cropping area have been extrapolated onto the data from Defra’s provisional 2019 UK June Survey to produce forecasted crop areas for the 2020 harvest. Already, they are now looking rather optimistic.

As it included the planting intentions as well as what was already drilled, it captured farmers’ then still eager plans to plant in late February and Early March. If, at that point, the weather had been anything near ‘normal’ for the time of year, then drills would be coming out early next week. But that was all ahead of the onset of Storm Dennis and before the full impact of Ciara was appreciated which jointly kyboshed that.

| Early Bird Survey (EBS): GB Crop Areas for Harvest 2020 – source AHDB | |||

| ‘000 hectares | DEFRA June Survey 2019 | EBS Forecast Harvest 2020 | % Y on Y change |

| Winter Wheat | 1,790 | 1,304 | -27% |

| Spring Wheat | 26 | 200 | +672% |

| All Wheat | 1,816 | 1,504 | -17% |

| Winter Barley | 453 | 347 | -24% |

| Spring Barley | 710 | 1,042 | +47% |

| Oats | 182 | 229 | +26% |

| Other Cereals * | 51 | 54 | +5% |

| Oilseed Rape | 530 | 361 | -32% |

| Other Oilseeds ** | 17 | 25 | +47% |

| Pulses | 178 | 226 | +27% |

| Arable Fallow | 224 | 336 | +50% |

| Other Crops on Arable Land *** | 719 | 756 | +5% |

| TOTAL | 4,880 | 4,880 | |

| * includes rye, corn and triticale, ** includes linseed & borage, *** includes s. beet, potatoes, vegetables, Maize (33%) and temp grass (20%) | |||

Much of those plans are now not likely to happen. Every day that rain continues to fall (and more is coming), is now gradually tightening the drilling window for spring cropping throughout so much of the UK.

Your Editor has spent much of this week (24th Feb onwards) travelling by train. If the views from the window are anything to go by, pretty much the entire country north of the M4 and south of Edinburgh are in a similar condition; flooded or saturated with sitting water on untended fields. Bales of straw still sit un-gathered in puddles of mud. For those fields that are drilled and the crop has emerged, it is becoming increasingly evident that most fields have large bare patches – up to 40% in some cases.

The water appears to have nowhere to go and the rivers are a rich brown, telling of the topsoil that has been washed away. We expect the soil structure of many fields, even those that have not had root crops, will be in a poor state and take a season or more to correct. In parts of central England, the only drilling since October has been on land that had cover crops on them. Perhaps this will be a lesson to the industry to consider these crops more seriously.

The Early-Bird Survey is undertaken each autumn to assess national cropping intentions. It is carried out by The Andersons Centre with the help of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants (AICC) and other agronomists. Over 80 agronomists took part in this year’s survey contributing over 615,000ha of arable land stratified across all regions of Great Britain.

The wheat area is forecast to fall by 9% which, if correct, would result in 1,645,000ha for harvest 2020, this would be the lowest wheat area since 2013. The spring wheat proportion within total wheat is seen rising a considerable 358%. It is thought that potentially half the UK winter wheat crop is still not planted though, so the decline could end up larger than the survey currently suggests.

The wheat area is forecast to fall by 9% which, if correct, would result in 1,645,000ha for harvest 2020, this would be the lowest wheat area since 2013. The spring wheat proportion within total wheat is seen rising a considerable 358%. It is thought that potentially half the UK winter wheat crop is still not planted though, so the decline could end up larger than the survey currently suggests.