It has been a challenging start to the 2024 season for many, to say the least. Persistent rain during and post-harvest has been followed by storms Babet, Ciarán and Debi, leading to some crop casualties already. For many, this year has marked the most significant challenge to the drilling campaign since 2019, although rainfall has largely been less persistent.

Andersons has compiled a crop condition assessment for the AHDB, summarised below in the order of planting.

Winter Oilseed Rape

Generally, the winter OSR crop can be split into three groups according to when it was planted. The earliest established crop is generally in good condition, having rooted into good moisture and developed well to stave-off pest pressure and subsequent rains. If anything, some of these crops are too far forward.

Crops established around the August Bank Holiday went into drier seedbeds, owing to the one week of very hot weather this year. These crops are in far worse condition, with cabbage stem flea beetle migrating at a similar time. Slugs have also been a significant issue, with mild evenings and wet weather. Many regions have already written off considerable areas.

The final group is the late-August/early September crop. This has generally established well, although root development was hampered by colder conditions and the crop isn’t as far forward as it should be. It remains to be seen how these crops get through the winter given some of thier poor rooting.

Generally, more OSR will be written off this season than normal. In addition, CSFB pressures are being seen further North and West than in a typical season.

Winter Barley

The winter barley crop was generally looking good, up until recent rainfall, having been established in reasonable conditions. That said, with some crops sitting in water-logged soils, yellowing has been seen. Crops should recover, although if biomass development is hindered,yield prospects may be too.

Given the moisture this autumn, good, stale seedbeds and weed control were achievable for many. Hopefully this will result in lower grass weed pressure than last year.

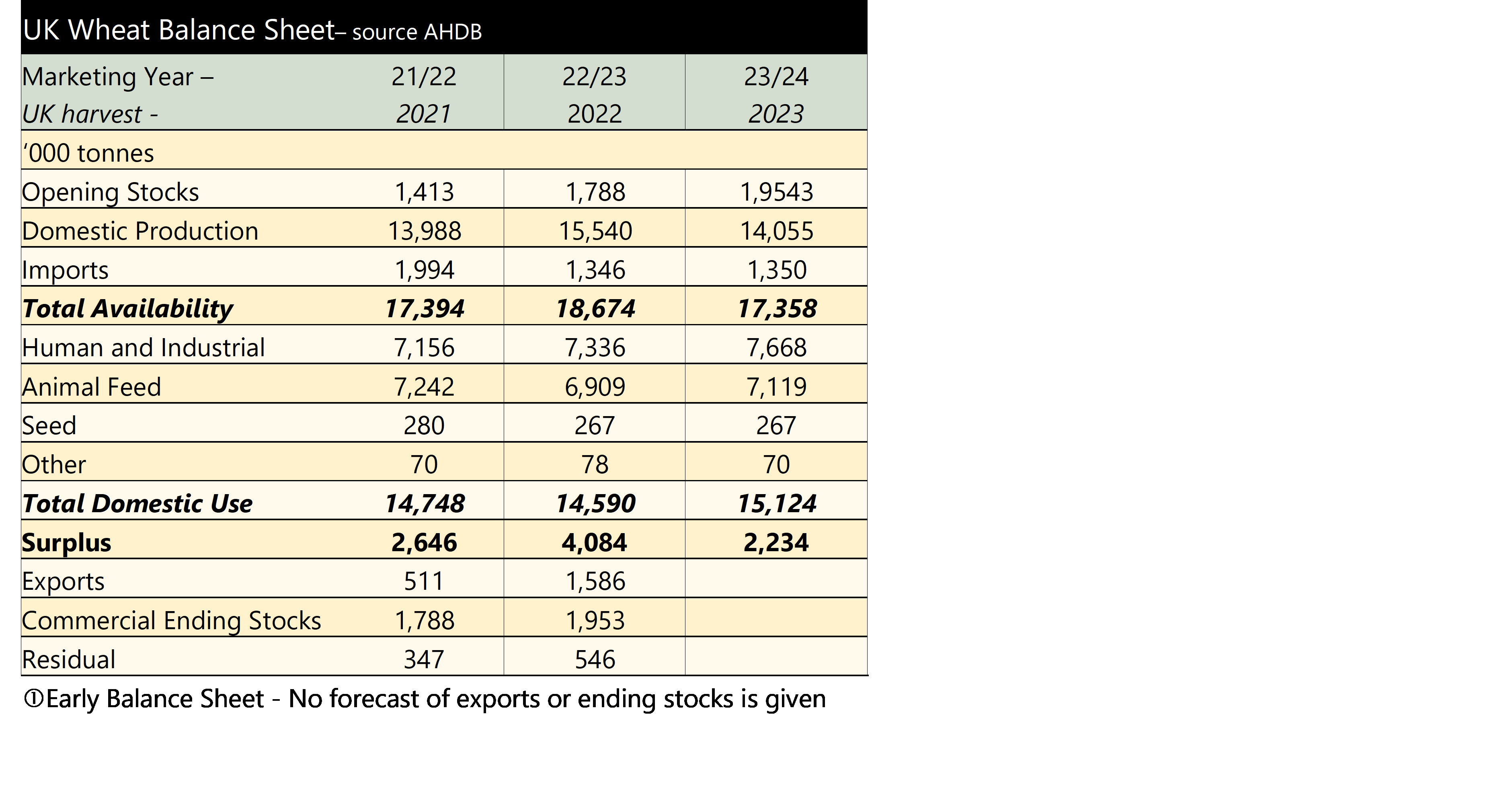

Winter Wheat

Wheat is undoubtedly the crop of biggest concern. Whilst the AHDB Early Bird Survey estimates a planted area of 1.698 million hectares, much of this will have been either undrilled or not very well established by the time the rains hit in October and November. Typically, by the end of October we would expect much of the winter wheat crop to be planted. Regional estimates of planting vary from 70% to 85% on average.

Concern over the potential for crop failure is reported across many regions by businesses of all sizes. Some of the worse hit wheat is in the Midlands and the North East, where there is expected to be a degree of write-off. What this crop is replaced with remains to be seen and will depend on how much of a field is written off. Where headlands and wetter patches are affected, there may be an effort to re-establish wheat. Failing that, a rise in fallow, or generally thinner, patchy, low-yielding crops are to be expected.

Pest pressure for wheat has also been considerable, with reports of the worst slug damage some have seen for 10 or more years.