Grain markets have been increasingly volatile in July, driven once again by the Black Sea. US maize crop conditions have improved, but weather concerns still linger.

Ukraine/ Russia

The renewal, or lack thereof, of the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI) has been a key watchpoint for grain markets for the past year. The agreement, guaranteeing the transit of agricultural commodities, broke down on 17th July 2023. The ending of the BSGI, came with missile strikes at the port of Odessa, and threats of military action against vessels delivering cargos to Ukraine.

In response to the ending of the BSGI, and subsequent concerns about global grain availability, UK feed wheat futures have been more volatile. Between 17th July and 19th July UK feed wheat futures (November 2023), gained more than £16 per tonne, before falling back by £5 per tonne.

The lack of the BSGI and exports through a key port such as Odessa is undoubtedly a challenge to global grain availability. However, reports from key commentators highlight the important role of the Danube and exports via Constanta, Romania, have played, and will continue to play, in keeping grain moving. An increase in Ukrainian grain being exported by road, rail and waterways through Eastern Europe could cause downwards pressure on grain prices in the countries bordering Ukraine. Some Governments have already placed restrictions on trade – for example grain can only transit through their territories.

The movement of Black Sea grain will continue to be a focal point. Further attacks on the Danube port of Reni lifted prices on Monday 24th July.

United States

Following last month’s update, the US Corn Belt has received much-needed rain. Drought as the crop moved towards silking negatively impacted crop conditions and was a risk to yield prospects.

Yield forecasts have been lowered but remain at record levels due to high planted areas. While weather remains a risk to the crop, the global supply and demand balance is little changed. In July, the USDA increased the area of maize it expects to be harvested by 900 thousand hectares.

The increase in the area of maize comes at the expense of soyabeans, with the area expected to be harvested falling by 1.6 million hectares. The cut to the soyabean area has added significant support to the wider vegetable oil complex, including rapeseed.

Hotter weather and less rain is forecast in the Corn Belt through the first week of August so conditions remain uncertain.

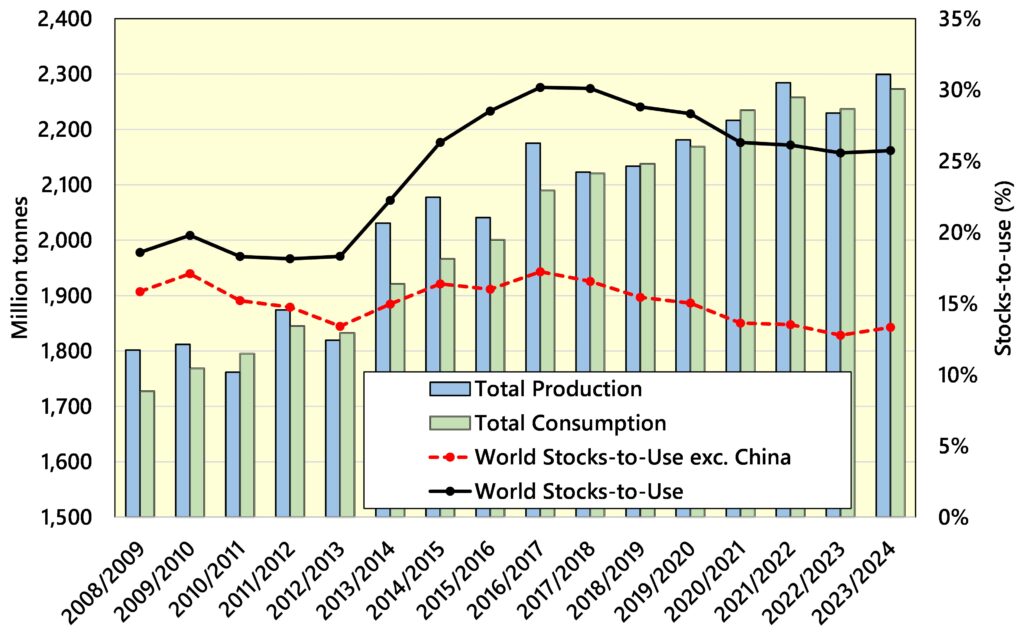

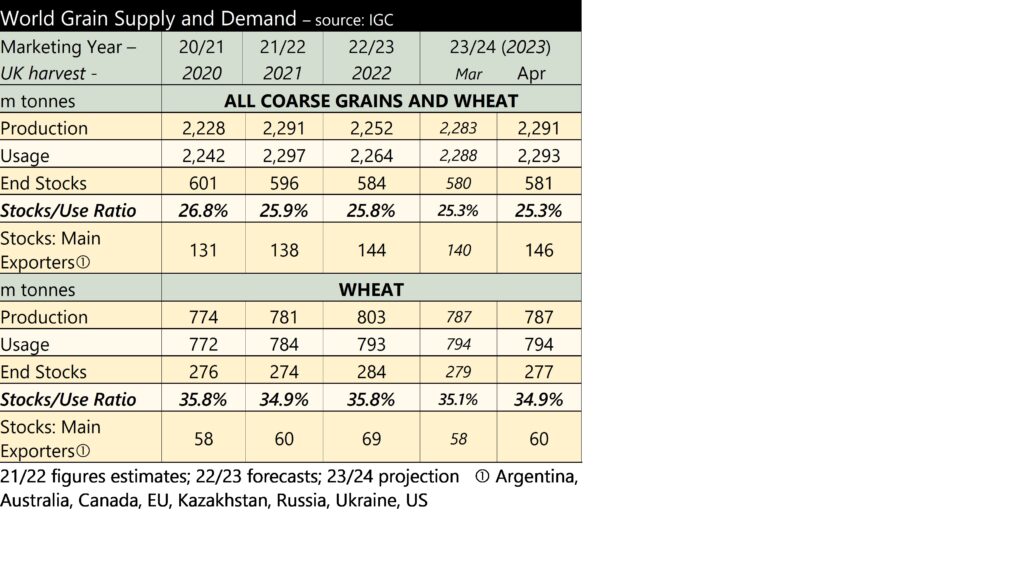

Global Supply and Demand

The latest global supply and demand figures highlight the continued view from the USDA that the world will be better supplied with grain this coming season. But there is a diverging picture between maize and wheat. Global maize stocks are forecast to grow by 17.8 million tonnes year-on-year. Meanwhile, wheat ending stocks are forecast to fall by 2.8 million tonnes; to the lowest level since 2015/16. Wheat production was estimated to decline further in July’s USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates, driven by month-on-month declines in Argentina, Canada, and the EU.