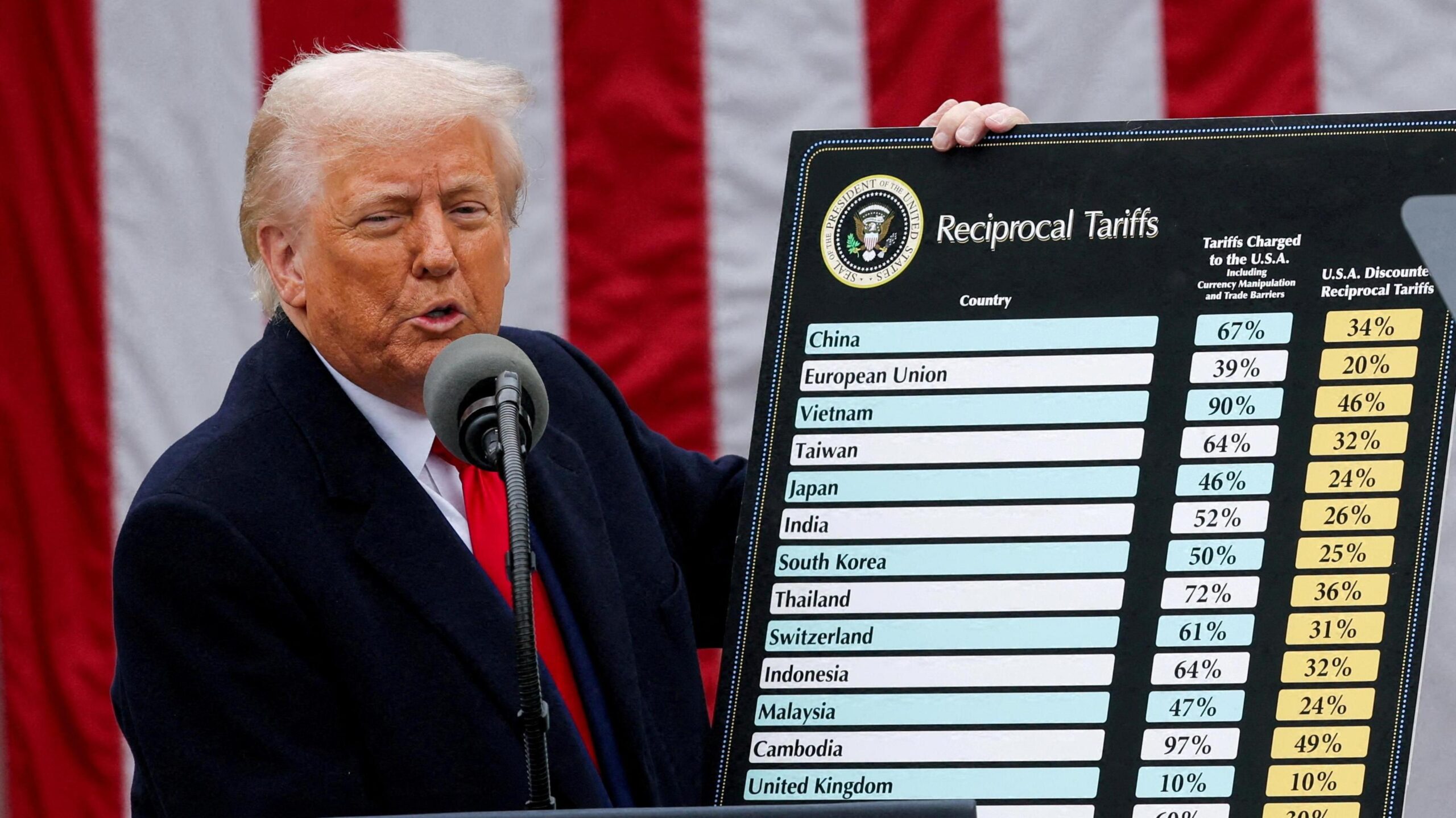

It has been a turbulent month in global trade circles following the US announcements on 2nd April of a swathe of new tariffs being imposed on all its trading partners, with the exception of Canada and Mexico (for most products). This included “universal tariffs” of 10% on most products (excluding key components such as semi-conductors, computer chips etc.), including agricultural goods. Some countries (including the EU (20% tariffs), Japan (24%) and South Africa (30%)) were going to be subject to higher tariffs, which the UK avoided (i.e. UK agricultural exports are subject to the universal tariff only).

Whilst President Trump announced a 90-day pause to the higher tariffs for most countries on 9th April, which has given a temporary reprieve to some, the universal tariffs are in operation. Moreover, for China, a full-scale trade war is now underway with imports of Chinese goods into the US, including agricultural products, now being subject to 145% tariffs. China has retaliated by imposing 125% tariffs on US goods, effective from 12th April and it has suspended imports of key agricultural products like soybeans and pork. In 2022-23, US exports of soybeans to China were estimated at $17.3 billion and from an agri-food perspective, the US exports significantly more to China than what China sends in the opposite direction. (Looking at all goods though China exports much more to the US than trade in the opposite direction).

Trade wars such as this cause significant upheaval on international markets, especially on companies trading directly between the US and China. However, the imposition of tariffs on goods effectively works as a tax on consumption which fuels inflation. Already in the UK, inflation has been trending upwards since the start of the year. The latest estimate (for March 2025) puts inflation (CPI) at 2.6% which is above the Bank of England’s 2% target. Whilst the UK has not imposed reciprocal tariffs on the US any increases in tariffs and associated trade wars are likely to give rise to inflation further down the line.

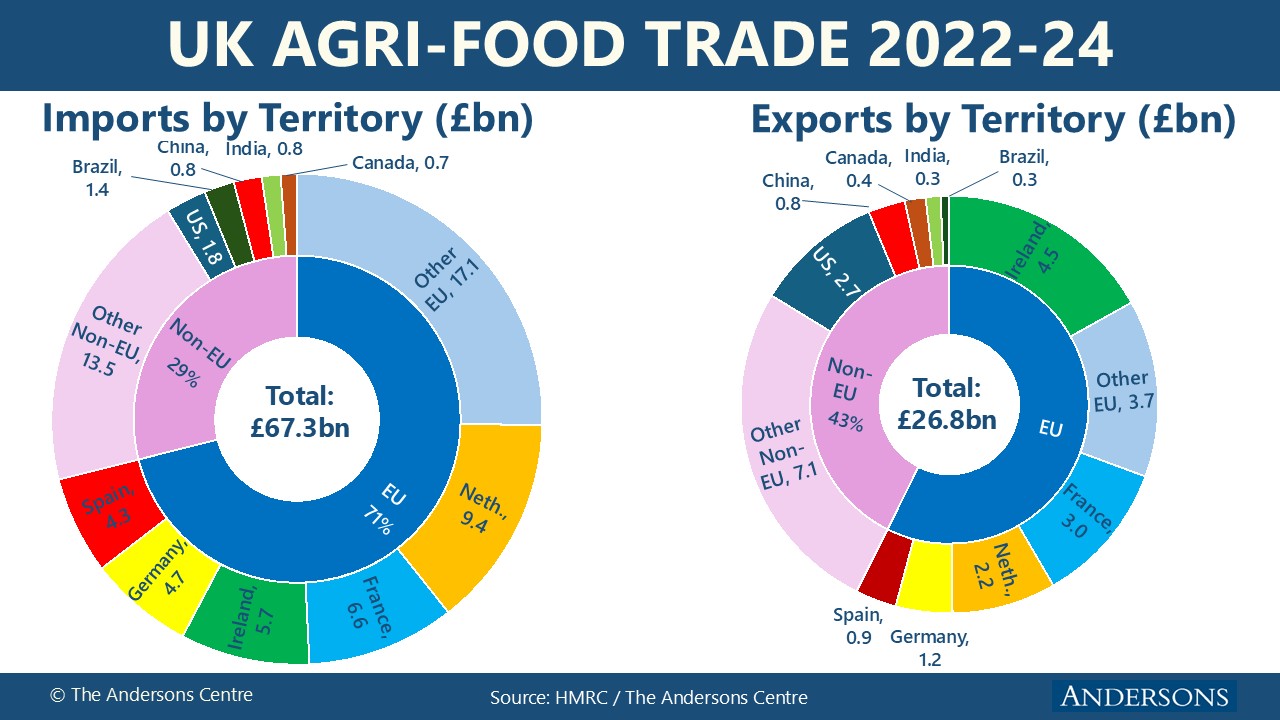

The 10% tariff will also affect UK exports of agri-food products to the US which we reported last month were estimated at £2.7 billion per annum during 2022-24. Within this, whisky exports are particularly significant and were valued at £971 million in 2024. Back in 2019, the previous Trump Administration imposed a 25% tariff on exports of Scotch whisky to the US, as part of a dispute between the US and the EU, which at the time included the UK as a Member State. Back then, the impact on Scotch whisky sales was significant but the tariffs were suspended when the Biden administration took office in 2021. This time around, there is also likely to be an impact on Scotch whisky sales although other countries (e.g. Japan) will also be affected.

The 10% “Trump tariffs” will also have some effects on exports of other UK products to the US including specialty cheeses. That said, other countries will be facing similar tariff levels and a 10% tariff is within the range of shifts in exchange rates which have been seen on trade from time-to-time. The Trump tariffs have weakened investor confidence in the US and as a result the Dollar has weakened noticeably. Since January, the Dollar has weakened from being worth 82 pence Sterling in January to 75 pence at present – 9% decline. This relative strengthening of Sterling will make UK exports more expensive in the US which will also act as a headwind. Conversely, Sterling has weakened slightly against the Euro (by about 1%) over the same period, which should help the competitiveness of UK exports to the EU, which is a much more important market for UK produce.

Overall, upheaval looks like being a continuing feature of international agri-food trade for the foreseeable future which will cause added challenges for global supply-chains and it looks like globalisation, as we have known it over recent decades, is undergoing a significant reversal.