In April 2019, a study undertaken on behalf of the AHDB was published which focused on the impact of Brexit on Farm Business Income (profit) and prices under two scenarios. The first is a UK-EU Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The second, a No Deal Brexit which incorporated the UK’s proposed WTO tariffs which it published in March. The study, led by Dylan Bradley and Professor Berkeley Hill was an update of similar work undertaken in 2017. It primarily focuses on English farms.

In addition to tariff impacts, the analysis also assumes that whilst direct payments in England would reduce by £150 million, public good payments would increase by the same amount, thus leaving the overall level of support unchanged. However, permanent non-UK labour would be restricted to 50% of current levels, although seasonal labour would continue to be supplied via a Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS). Trade facilitation costs as a result of non-tariff barriers would also ensue, costing 2% for crops and 5% for livestock in an FTA scenario and rising to 4% for crops and 8% for livestock under a No Deal.

In general, Farm Business Incomes (FBI) fall under both an FTA and a No Deal (WTO) scenario. Under an FTA scenario, the effects are most pronounced in general cropping (-30%), dairying (-18%), pigs (-42%) and cereals (-19%). A key explanatory factor for these farms is the increase in labour costs associated with less permanent labour availability. However, beef and sheep is an exception where incomes remain close to the baseline level.

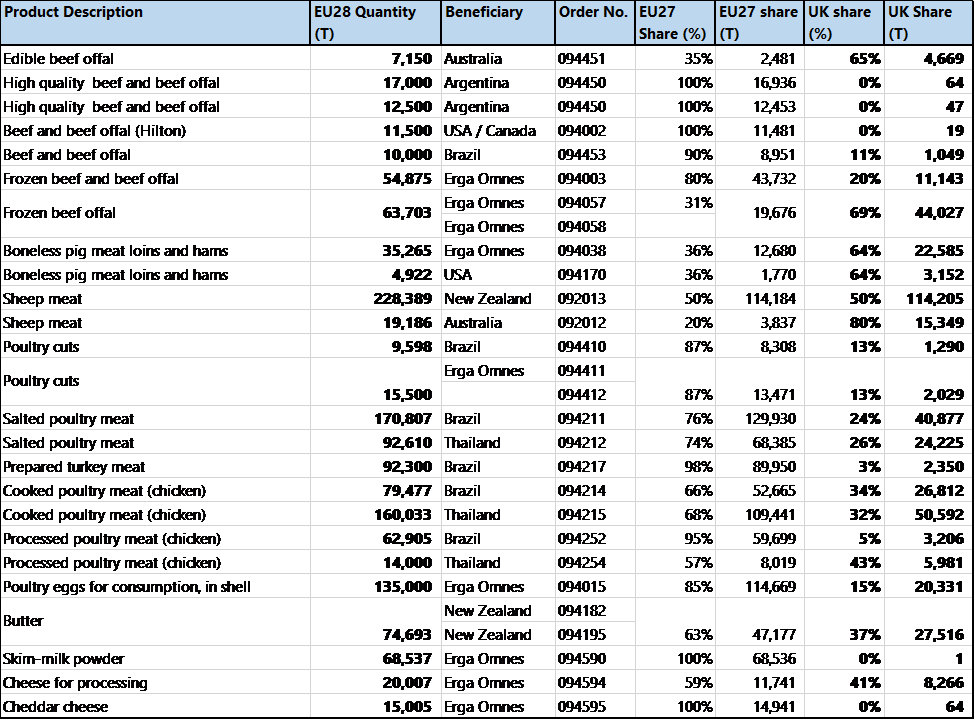

Under the WTO scenario, FBI falls further across all sectors. Cereal farm income declines by 29%, general cropping incomes are 35% lower than the baseline and dairying incomes are 22% lower. It is also under this scenario where beef and sheep (both lowland and LFA) also decline significantly, by approximately 50%. Across all farm types, production revenues decline with the impact of tariffs being particularly problematic for sheep production. In the beef sector, the imposition of a new 230Kt tariff rate quota (TRQ) for imports, which would be available to a everyone (i.e. EU and non-EU countries), would seriously erode farm-level prices. The projected price impacts as a result of the modelling undertaken in this study, as summarised by the AHDB, is set-out below. However, it must be borne in mind that the modelling process used to derive these calculations are acknowledged by the authors as being a considerable simplification of reality.

Unsurprisingly, given its exposure to the EU market in terms of exports, the most pronounced price decreases are in the sheep sector with declines of 5% (FTA) and 25% (WTO) forecast. For beef, a 4.3% rise is projected under an FTA scenario, mainly due to trade-facilitation impacts but a 4.6% decline is projected under WTO as lower cost imports from the world market exert a negative influence. Some increases are also forecast for wheat under both scenarios and are again a reflection of trade facilitation costs. In contrast, barley prices are forecast to decline and here restricted access to the EU market for barley exports in particular are influential, especially under a WTO scenario where market access would be subject to tariffs and access for malting barley exports via TRQ which would be heavily restrictive. As a result, the areas of wheat are projected to increase at the expense of barley, subject to agronomic constraints. The prospects for milk prices are more positive with rises projected across both scenarios as imports from the EU become less competitive due to trade facilitation costs.

| Sector | UK-EU FTA | WTO Scenario: UK Tariff Schedule |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat | +2.3% | +3.6% |

| Barley | -2.0% | -12.1% |

| Oats | +0.1% | -3.0% |

| Oilseed Rape | -2.0% | -4.0% |

| Potatoes | +1.8% | +3.6% |

| Carrots | +1.2% | +2.4% |

| Sugar Beet | +0.8% | +1.1% |

| Milk | +2.6% | +3.8% |

| Beef | +4.3% | -4.6% |

| Sheep | -5.0% | -25.0% |

| Pigs | +3.4% | -4.8% |

| Poultry | +1.5% | +2.3% |

| Livestock feed | +0.7% | -0.8% |

| Poultry feed | +1.3% | +1.1% |

| Fertilisers | +0.9% | +4.9% |

Source: AHDB (2019) and Bradley and Hill (2019)

Overall, the study’s findings suggest that restricted labour availability could have a major impact on farm profits even if the trade impacts under a Brexit Deal scenario are limited. This highlights the importance of labour to food and farming generally and shows that adequate access to labour, whether it is from the EU or elsewhere, will continue to be crucial. Other studies assessing trends in farm-level costs have shown that overheads have risen substantially in the past decade and that effective control of these costs is crucial to farm profitability.

Further information is available via: