Overall Comment

Whilst in some counties over the last week the weather has been harsh, over the country it appears overall, December has so far been considerably ‘less wet’ than the previous 3 months. But with soils already saturated it does not take much to keep the land impassable. Now the crops are mostly dormant meaning nothing is transpiring the water away, and minimal evaporation is taking place either as temperatures are too low with high humidity. In other words, a millimetre of rain here and there has been topping up the already sodden soils. Cold dry frosts have also been scarce this autumn, meaning that grain conditioning in store has been difficult. Some samples, particularly of barley have been losing premiums because of infestations. Managing grain quality will become increasingly difficult this winter.

Wheat

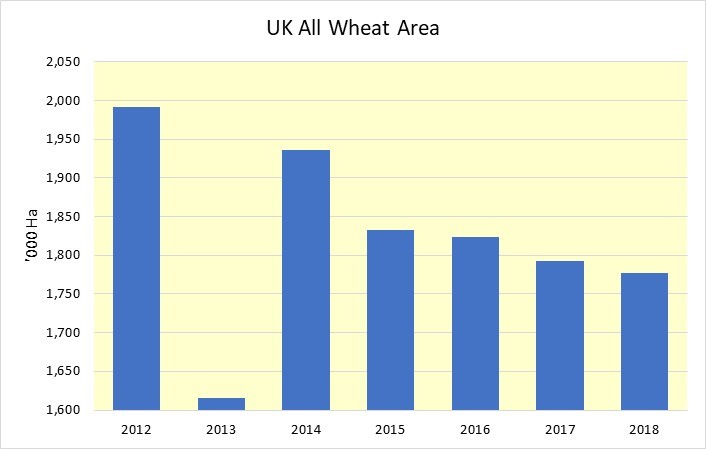

Nevertheless, the AHDB has reported they consider the winter wheat planted area has now risen to about 60 of intended plantings, suggesting progress of about 5% since the last of these bulletins was published. Clearly, at this rate, and if weather conditions do not change, there will still be about 30% of the planned winter wheat area undrilled at the end of February; about the end of the window available for drilling most of the varieties currently sat in bags in farm barns around the country.

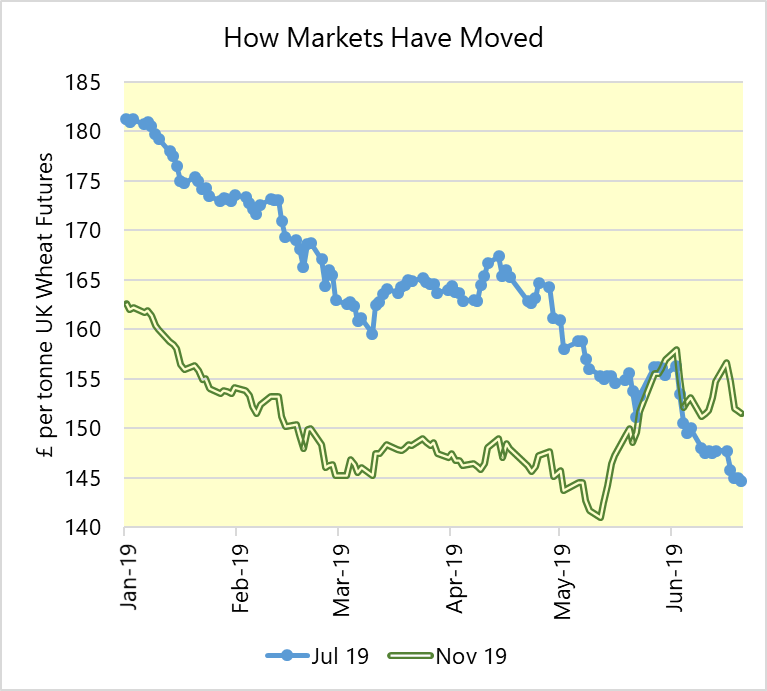

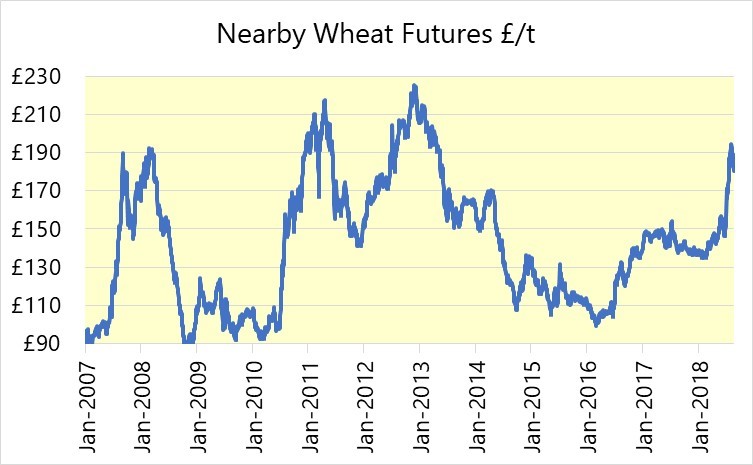

UK grain traders have had a challenging time this season, unable to book grain exports past the official Brexit dates. For a year with a large crop to sell, this has affected market prices. Perhaps some clarity in the New Year will facilitate the rest of the marketing campaign.

Barley

Old crop markets are asleep already in preparation for the Christmas break. Its not even planted yet, but the prices for the 2020 crop have not been great, with expectations of very large UK and EU crops. Few buyers are buying much new crop yet, as prices are so bearish. Certainty regarding the EU departure will support the buying confidence. Seed traders have been gathering what spring barley tonnages they can and, between them, it appears there is enough available for in excess of a million hectares to go in the ground, as soon as conditions allow. This would be the highest spring barley crop since 1988, and the largest total barley crop since 1990; that is, assuming it is dry enough to drill by then.

Oilseed Rape

Global demand for vegetable oils is strong. The Chinese still demand vast tonnages of soybeans, despite millions of its pigs, who et the meal) have been slaughtered because of African Swine Fever. This might shift the balance of demand between oil and meal which would favour crops like oilseed rape that have a higher oil content. Certainly, oilseed rape has done quite well over the last month, regardless of the overall movements of sterling.

Pulses

Pulses trade quickly in the first half of a marketing year, then slow down for the second half. The export market for pulses for this season is quickly reaching that point, partly as the Australian crop will be competing strongly come January, and also because of customs clearance deadlines in North Africa.