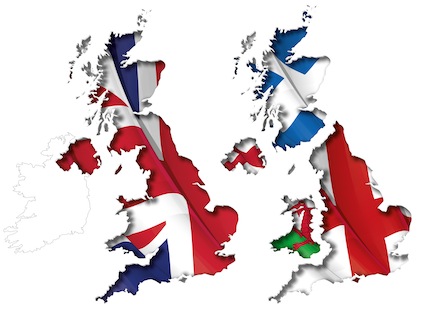

The UK Government has published a White Paper on how the UK internal market (UKIM) will operate in the future. Due to devolution, some policy areas (e.g. fiscal and monetary policy, State Aid) are ‘reserved’ for the UK Parliament whilst some 160 others, most notably agri-food and fisheries, environment and planning as well as product standards for agri-food products are devolved competences. When the UK was a part of the EU Single Market, it provided the legal framework to enable goods and services to flow freely. However, with Brexit, policy-setting powers will be ‘returned’ to the devolved administrations, leaving open the scope for greater divergence within the UK. The UK Government’s White Paper seeks to address this and forms part of a four-week consultation period and the UK Government aims to fast-track legislation from September. In developing the UKIM system the UK Government aims to:

- Continue frictionless trade between all parts of the UK

- Continue fair competition and prevent discrimination

- Continue to protect business, consumers and civil society by engaging them in the development of the market.

To achieve these aims, the white paper proposes a four main types of measures:

- Common UK Frameworks: designed to support the functioning of the UKIM, the management of common resources and the UK’s ability to negotiate, enter into and ratify trade and other international agreements. This includes setting a baseline of regulatory coherence across the UK.

- Market Access Commitment: would enshrine into law two key principles: ‘mutual recognition’ and ‘non-discrimination’ which would enable UK companies to trade unhindered across the UK. This could mean that products supplied in one part of the UK (e.g. England) which are produced to different standards than other parts of the UK, could still be offered for sale across the entire UK market. This proposal has ignited tensions. The SNP for instance fears that if English standards are lowered, it will erode Scottish standards. Furthermore, as Northern Ireland will be applying EU regulations, products deemed not to be meeting the EU’s standards will not be permitted to enter. The Paper acknowledges Northern Ireland’s commitments under the Irish Protocol but re-emphasises that Northern Ireland will have ‘unfettered access’ to the GB market. Whilst the UK Government is seeking to make NI’s access to the GB market as frictionless as possible, the reality is that additional regulatory requirements will need to be adhered to (e.g. Summary Declarations). Some business groups are seeking compensation or mitigation measures the impact of such friction but are awaiting further details from Government on how to do this.

- Uniform subsidy control regime: legislated for in the UK Parliament (as State Aid is a ‘reserved’ matter). That said, EU State Aid regulations would continue to apply in Northern Ireland with respect to goods as a result of the Protocol. Services would be applied based on the UK regime.

- Independent advisory group and intergovernmental responsibilities: whilst the evolution of the UKIM will be overseen by the UK Parliament, the White Paper stresses the scope for expanded intergovernmental arrangements. These will help to monitor the health of the UKIM and will help to gather evidence for its future development. There is also the possibility of an independent advisory body being set up to examine how the UKIM should evolve but these ideas are not fully developed yet.

Although the Paper emphasises the UK’s commitment to maintain its high standards, like a lot of Government publications, its language could be open to differing interpretations (e.g. “committed to promoting robust food standards nationally and internationally, to protect consumer interests”). On the one hand, this could mean upholding the current standards inherited from the UK’s EU membership. Alternatively, it could signify a move to evolve standards so that they are more aligned with those applicable elsewhere internationally if that is what (some) consumers want. Whilst it acknowledges that any changes to food safety legislation would need to be brought before the UK and devolved Parliaments, the Market Access Commitment arguably leaves open the possibility the products deemed acceptable for import into England could be placed on the market in Scotland or Wales.

The White Paper cites a coherent UKIM system as being particularly important for future Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). This is because it would make the UK as a whole more attractive for countries to do business with it and claims a coherent framework would ensure that the UK as a whole would benefit from such FTAs and would enable UK businesses to compete internationally.

Finally, it must be emphasised that without the proper regulatory framework, the coherence of the UKIM could easily unravel. From 2021, one part of the UK (i.e. Northern Ireland) will be applying a different regulatory framework. The greater the divergence between the UK and the EU in the future, the more challenging it will be to maintain UKIM coherence. This will present significant hurdles for many aspects of agri-food regulation such as food standards and GM. Until the post Brexit regulatory framework has bedded in and a new ‘steady state’ emerges with respect to the UK-EU trading relationship, it would be sensible for the UK to choose to have ongoing regulatory co-alignment with the EU. This could then be reviewed in a few years’ time if required.