In recent weeks, there has been a noticeable increase in the pace at which the Department for International Trade (DIT) is seeking to conduct negotiations on free-trade with non-EU countries. In addition to the highly-publicised negotiations with the US which commenced in mid-May, talks have also commenced, or are about to commence, with Australia & New Zealand and Japan. This is in addition to negotiating ‘Continuity Agreements’ with various countries so that the UK can continue to trade with them after 31st December 2020 as it did when it was an EU Member State.

UK-US Trade Negotiations

When the UK set out its negotiating objectives for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the US back in March, it noted that US-UK trade was valued at nearly £221 billion and accounted for nearly 20% of the UK’s exports. It claimed that, as a result of an FTA between both countries, trade could increase by £15.3 billion in the long-run. It is therefore seeking to secure a comprehensive and ambitious FTA with the US, but was also keen to emphasise that it ensure high standards and protections for British consumers and workers. This contrasts with the US negotiating objectives published in February 2019 which seek to ‘promote greater regulatory compatibility to reduce burdens associated with unnecessary differences in regulatory standards’ and to eliminate ‘unjustified trade restrictions’ (including labelling) that affect ‘new technologies’.

Although the UK Government have noted potential gains that could be achieved for British agriculture (e.g. increased access for lamb and cheese exports to the US), most debate has centred on the potential threat posed by permitting imports from the US which do not meet the standards that British farmers (or imports from the EU and elsewhere) currently adhere to. In addition to issues posed by chlorinated chicken, there are also concerns around hormone treated and lactic-acid washed beef finding its way into the UK market. It raises the prospect of UK farmers having to continue to adhere to current high standards on animal welfare and the environment whilst simultaneously being subject to competition from US importers producing to lower standards.

Whilst the UK Government might claim that it will seek for global food standards to be raised at the WTO level, relative to the US it is a small economy. The US accounts for 23.7% of global GDP whilst the UK accounts for 3.4%. Bargaining power is always crucial during trade negotiations and this dynamic becomes even more pronounced under an ‘America First’ US Presidency. The threat to UK food standards is very real. An FTA that permits significant volumes of US produce, produced to US standards, to enter the UK market would seriously erode the competitiveness of the British farming industry, not just domestically, but also in terms of exports to the EU. For example, each year between 25% to 40% of the UK lamb crop is exported, almost entirely to the EU, which are valued at approximately £350 million per annum. An FTA that gravitates towards US standards will significantly reduce access to the EU. Increased access to the US market via UK-US FTA will not compensate. For instance, the DIT estimates that lamb exports to the US would increase be £18m.

Australia and New Zealand Negotiations

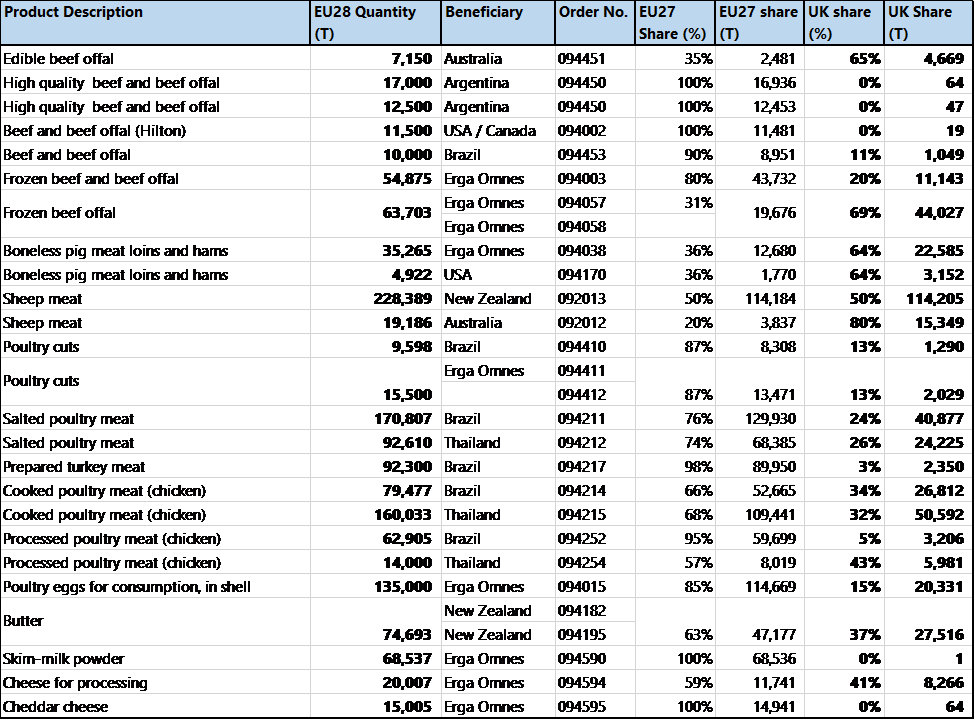

On 17th June, the UK formally announced its objectives for the upcoming trade negotiations with Australia and New Zealand. Again, agriculture is likely to feature prominently, especially given the historical trading relationships which existed before the UK joined the EEC.

Another major focus of these negotiations will be the reduction in non-tariff barriers to trade as New Zealand in particular has embraced e-certification. New Zealand’s standards are quite close to the status quo in the UK (and the EU); therefore its non-tariff barrier costs are already low for several products (e.g. lamb).

It is likely that increased access for beef, lamb, dairy and horticultural products will be amongst the key asks from Australia and New Zealand. This would bring about increased competitive pressure on UK farmers but it is not attracting as much controversy because both countries’ production standards are perceived to be more acceptable than the US for example. Geographic distance from the UK also limits their influence. Indeed, both countries have been focusing more heavily on Asia in recent years.

From the UK side, its focus is on increased access for services, investment and digital trade. Opportunities on the agri-food and drinks side appear to be limited to niche sectors such as the export of British sparkling wine and chocolate.

Japan Negotiations

These talks also commenced recently and, given that Japan recently concluded an FTA with the EU (which at the time included the UK), it is anticipated that such negotiations would be wrapped up quickly. The Japanese Government is pushing for the talks to be concluded in approximately six weeks as it claims it needs to secure Parliamentary approval during the autumn session in order to be ready to become applicable in January. The UK had initially hoped that it could roll-over the existing EU-Japan FTA into a UK-Japan equivalent, but the Japanese Government has sought separate negotiations in what is seen as a bid to secure greater concessions from the UK. Like most FTAs, agriculture is a key issue. Since the completion of the EU-Japan FTA, the Japanese Government has come under pressure from its highly protectionist domestic farming lobby to limit access to its market for agri-food. The Japanese are also keen to secure the supply chains of its companies which use the UK as a base to supply into the EU so it is likely that it is also using these negotiations as leverage so that the UK secures a trade deal with the EU.

The UK Government claims that a UK-Japan FTA could increase trade between both countries by over £15 billion and that the UK economy could see a £1.5 billion benefit. It remains to be seen what specific concessions Japan will seek on agri-food. The UK already exports significant volumes of grain (e.g. wheat and barley) to Japan. Export opportunities also exist for products such as whisky.

Other Negotiations

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP): the UK has also reaffirmed its interest in becoming a member of the CPTPP which is one of the world’s largest free trade areas accounting for 13% of global GDP in 2018. The CPTPP includes Japan, Australia and New Zealand amongst its members and negotiations with these countries are seen as a stepping stone towards joining this larger trade bloc which also includes Canada, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore and Vietnam.

- Continuity (Rollover) Agreements: with the UK leaving the EU, it is seeking to replace the FTAs which the EU had agreed with other countries whilst the UK was still a Member State. To this end, it has been pursuing Continuity Agreements with these countries. To date, agreements have been concluded with approximately 50 countries, including Switzerland, South Korea, Chile and South Africa, as part of the South Africa Customs Union and Mozambique (SACUM) trading block. Negotiations are ongoing with 16 others, including Canada, Mexico and the Ukraine. Such rollover agreements are anticipated to have a limited impact on agri-food as they are largely seeking to replace FTAs that the FTA was subject to as part of the EU.

Whilst pursuing trade deals around the world is a crucial aspect of the UK’s independent trade policy, one must not lose sight of the fact that exports to the EU (£300 billion) accounts for 43% of total UK exports. Furthermore, imports from the EU, which accounts for 47% of the UK’s total, plays a crucial role in the supply-chains of numerous companies. Any major disruption in the supply of inputs would inhibit UK manufacturers’ ability to assemble finished products for export. This is also true within the agri-food sector. Therefore, securing a comprehensive FTA with the EU should continue to be the priority. This can be done whilst also securing FTAs elsewhere but a considered approach must be taken.

A key danger is that the UK Government agrees trade deals in haste and that this could come back to haunt the UK in decades to come. The global geopolitical tectonic plates are shifting quite rapidly. The danger of a new Cold War, between the US and China is emerging. Trade between both countries could become seriously curtailed. The US is already a big agri-food exporter to China. If it needs to look elsewhere, the UK will be a key target market.

In any trade deal there are (excuse the pun) trade-offs between different sectors to get an agreement. The danger is that agri-food might be sacrificed to allow trade gains elsewhere.