Like the water sat on many headlands around the country, old crop wheat markets could rightly be described as stagnant!

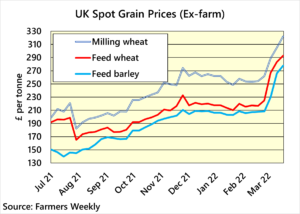

Looking back across the May-23 UK feed wheat futures market, prices have been stuck in a channel from £194 to £204 per tonne since the beginning of September. Prices are sitting in the bottom of that band presently and showing little sign of moving back towards the top. This is partly driven by readily available Black Sea grain, keeping prices pressured.

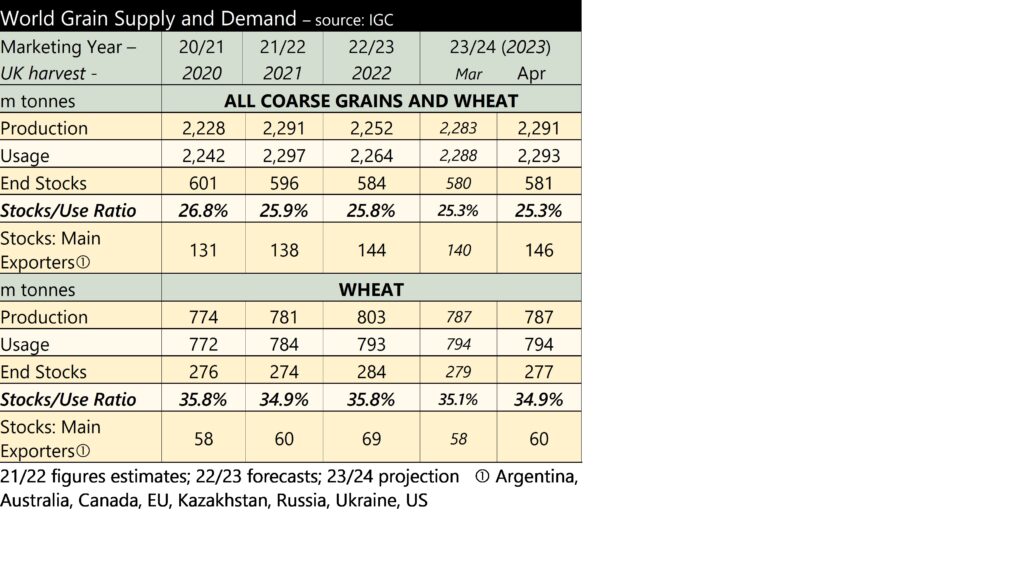

The old crop market is also influenced by a large global maize crop, with the US harvest all but complete. In November, the USDA added a further four million tonnes to its production forecast for the US, citing improved yields. In total a further 2.5 million tonnes have been added to global maize ending stocks, compared to October’s forecast. Ending stocks of maize, globally, are up 15 million tonnes year-on-year.

The new crop market is more interesting, unless you are looking out on waterlogged crops. Poor weather conditions have led to estimates of a 5-10% decline in wheat area across the UK, France, Germany, and Ukraine (Openfield). This is driving an £11 per tonne premium for November 2024, over current May prices. Concerns are built into new crop pricing. It will take a worsening of conditions to keep prices supported.

In the UK, grain markets are lacking activity. There are reports of weaker demand for bioethanol production. UK wheat prices are uncompetitive in export markets and prices are under pressure (see Key Farm Facts). Milling premiums remain elevated.

Feed barley is at a more than £20 per tonne discount to feed wheat. However inclusions in animal feed rations are already high. As such, barley prices need to be competitive into export markets to generate extra sales. Old crop malting barley premiums remain high. With concern over winter wheat plantings, and a subsequent increase in spring barley plantings likely, new crop premiums may be lower.

Oilseed rape prices are benefitting from uncertainty over planting of soyabeans in South America. The north of Brazil remains very dry, while planting progress in the south of Brazil has been delayed by heavy rains. The pace has improved towards the end of November but remains behind average. While this is supporting oilseeds now, it could also hinder the maize plantings which follow soyabeans in spring, offering future support to grains.

A week is a long time in politics, and given their intertwined nature at present, so too in grain markets. As the war in Ukraine enters into its second month, the impact on grain and oilseed markets has been considerable. This is not surprising when we consider the reliance the world has on both Ukraine and Russia for grain and oilseed supplies.

A week is a long time in politics, and given their intertwined nature at present, so too in grain markets. As the war in Ukraine enters into its second month, the impact on grain and oilseed markets has been considerable. This is not surprising when we consider the reliance the world has on both Ukraine and Russia for grain and oilseed supplies.

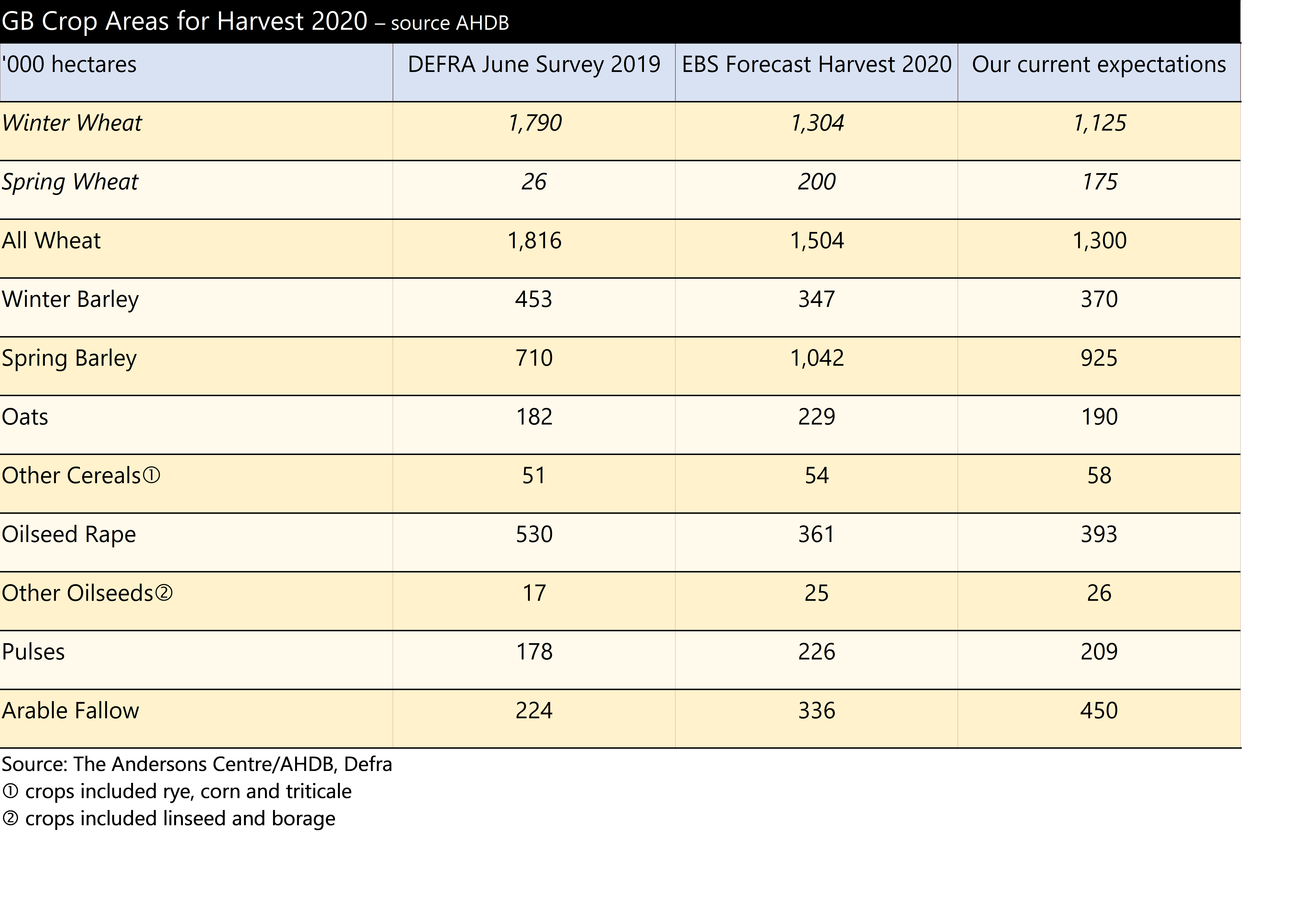

If this projection is correct, it would leave potentially the lowest wheat area planted in the UK since 1978/79, and the highest spring barley area since 1987/88. Some projections expect spring barley to exceed 1 million hectares but we are not convinced there is enough time for that to occur. Oilseed rape area might end up being the lowest since 1988/89. Even so, it still might be the highest we see again because the difficulties of growing the crop this year have been only partly because of the rain, and partly because of the flea beetle. The fallow land area we have suggested here would be the highest level since set aside was mandatory back in 2007. For 2020 autumn drilling and the 2021 harvest, we would expect a high proportion of farmers very keen to capitalise on the first wheat opportunity, possibly planting a little earlier than this year too. Hold tight for a big wheat crop next year.

If this projection is correct, it would leave potentially the lowest wheat area planted in the UK since 1978/79, and the highest spring barley area since 1987/88. Some projections expect spring barley to exceed 1 million hectares but we are not convinced there is enough time for that to occur. Oilseed rape area might end up being the lowest since 1988/89. Even so, it still might be the highest we see again because the difficulties of growing the crop this year have been only partly because of the rain, and partly because of the flea beetle. The fallow land area we have suggested here would be the highest level since set aside was mandatory back in 2007. For 2020 autumn drilling and the 2021 harvest, we would expect a high proportion of farmers very keen to capitalise on the first wheat opportunity, possibly planting a little earlier than this year too. Hold tight for a big wheat crop next year.