The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) is continuing to experience ‘teething problems’. This is perhaps hardly surprising as the agreement (click here for summary) was only agreed on Christmas Eve, with implementation beginning just over a week later. From an agri-food perspective, these difficulties primarily relate to the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) issues which are examined below. Rules of Origin have also caused upheaval, but this issue was examined in a previous article (click here).

NI Protocol

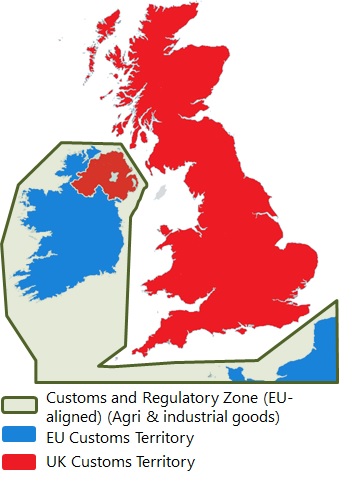

Goods shipped from GB to NI are now subject to EU customs and regulatory controls upon entry into Northern Irish ports (e.g. Belfast and Larne). It was obvious that difficulties would emerge both in terms of logistics but also from a political perspective. Although some grace periods are in place, varying from 3 to 12 months, many businesses were unprepared for the new regulatory requirements. There were numerous reports of GB-based firms being simply unaware of the new customs and SPS requirements. This caused substantial delays in some cases. Given the difficulties which have arisen, there was a meeting on 18th February of the Joint Committee overseeing the implementation of the Protocol and NI business groups. The UK Government was represented by Michael Gove whilst the EU Commission was represented by its Vice President, Maros Sefcovic. NI business groups called for pragmatism and are seeking the following;

-

- Grace period extensions: to permit traders to have a longer timeframe to adapt to the changes set out in the Protocol. This, they claim, would help to reduce pressure on supply-chains and give greater certainty to businesses that trade between GB and NI.

- Veterinary agreement: between the UK and the EU to reflect the low risk involved as both parties’ standards are effectively the same, particularly on trade from GB to end-users in NI.

The veterinary agreement issue is examined in further detail below. It remains to be seen what the UK and the EU will be able to agree on the NI Protocol. Michael Gove had already called for a grace period extension until 2o23. The recent appointment of David Frost (previously Chief Brexit Negotiator) to the Cabinet to oversee UK-EU relations, a role which will also cover the NI Protocol, will add an uncertain dynamic as the Gove-Sefcovic working relationship had functioned quite well. It remains to be seen what the EU will offer, but it is obvious that businesses need significantly more time to adapt and that rising political tensions need to be quelled.

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Issues

There were minimal easements in the SPS area within the TCA. This, in addition to the EU implementing its border controls fully from January, meant that UK exporters were suddenly faced with a substantial increase in paperwork with only a few days’ notice. Some have reacted by limiting the number of consignments being shipped to the EU until they get a greater understanding of how the procedures work. There have been reports of hauliers being unwilling to depart warehouses, processing plants etc. until the paperwork for each shipment is in order. As a result, port traffic volumes are lower than normal. Holyhead-Dublin volumes are at 50% of normal levels. Dover-Calais volumes are also down, but some recent evidence suggests they have been recovering in comparison with the drops witnessed in January. As freight volumes increase during the spring, as is traditionally the case, border control systems are going to be tested. Especially as additional certification and checks will be required on imports into the UK from April and will become fully operational in July.

Already there is evidence of insufficient veterinary capacity at ports. This creates backlogs for shipments needing to undergo physical checks. These are effectively the same as the levels of checks that countries trading with the EU on WTO MFN terms experience. Such checks, when coupled with sampling in some instances, can result in significant delays and create a major risk of product value deterioration.

To address this issue and the difficulties arising from the NI Protocol, the prospect of a UK-EU SPS (veterinary) agreement has been mooted. Here, there are two potential options:

- ‘Swiss-style’ SPS agreement: where the UK would align with, and follow, the EU’s standards as they evolve in future. The Ulster Farmers’ Union (UFU) has stated that it would support such an arrangement.

- New Zealand-style agreement: where physical checks on red meat shipments for instance will be lowered from 15% to 1% to reflect the low risk levels and high alignment in standards.

The EU has stated that a veterinary agreement is ‘on the table’, however, they would envisage this being based on alignment with EU standards (i.e. Swiss-style). Given the importance that the UK placed on sovereignty during the negotiations, it is unlikely to opt for this approach, particularly with David Frost at the helm. However, a New Zealand-style agreement might be viewed more favourably. Whilst this will not obviate the need for some border controls, particularly on GB-NI trade, if these could be moved in-land for ‘authorised (trusted) traders’, it would reduce the visibility of such regulatory checks to a significant degree.

Whatever form a potential veterinary agreement between the UK and the EU would eventually take, the UK will insist on having the right to diverge in the future, if it so wishes (e.g. to do a trade deal with the US). In such a scenario, the UK would give a notice period (e.g. the EU-NZ agreement has a 6-month notice period) and it would then be likely that SPS controls would revert back to the current default, with some additional arrangements under the NI Protocol.

What is increasingly clear is that the UK-EU relationship will be continually subject to negotiations. In effect, the ‘teething problems’ are more like a permanent toothache and will require constant attention to keep their impact to ‘manageable’ levels. The appointment of David Frost to the Cabinet confirms this. Therefore, one should not see the ending of the Transition Period in January as the ‘end of Brexit’, perhaps it is more like the ‘end of the beginning’ of the new era of UK-EU relations.