Although activity in Westminster and Brussels is usually subdued during the August holidays, this year it is more of a sense of calm before the storm as the Brexit process is expected to reach its climax in October. That said, there have been several noteworthy developments in recent weeks from an agri-food perspective.

Government’s No-Deal Brexit Preparations

Since coming to power last month, the Johnson Government has ramped up its preparations for No-Deal considerably.

On 21st August, the Chancellor announced that HMRC is automatically registering over 88,000 VAT-registered companies to be allocated an Economic Operator Registration and Identification (EORI) number. This enables businesses to be identified by Customs authorities when conducting overseas trade. This is very much the first step required for businesses to continue trading with EU Member States post-Brexit and affected companies should start receiving notification letters in the coming days. For businesses that trade with EU Member States which are not VAT-registered, and do not currently have an EORI number, they will still need to register if they wish to continue trading with the EU. Further information on doing this can be found via; https://www.gov.uk/eori

For businesses trading in live animals and animal products, the Government has also published additional guidance on importing from, and exporting to, the EU (and countries such as Switzerland, Norway and Iceland which are also considered to be covered by EU trade). The following link lists the various certifications and approvals required when importing into Great Britain from the EU; https://www.gov.uk/guidance/moving-live-animals-or-animal-products-as-part-of-eu-trade

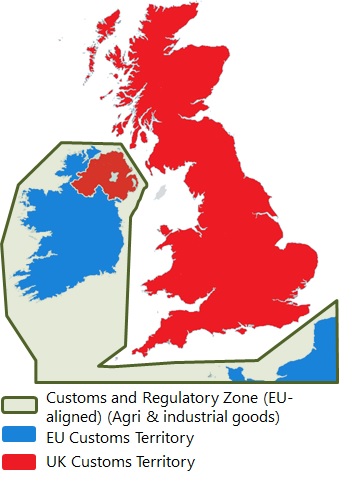

Earlier in the month, a leaked Government document on the Government’s No-Deal preparations reported by The Times (dubbed ‘Operation Yellowhammer’) suggested that the UK would face shortages of food and fuel in the short-term as there would be considerable delays at Ports as well as the re-imposition of a Hard Border in Ireland. The Government subsequently claimed that the report was dated and that significant steps to prepare for a No-Deal Brexit have been taken since.

Whilst it is evident that the Government is ramping-up its preparations, it is also apparent that a No-Deal Brexit would cause significant upheaval in its immediate aftermath. Although this could bring some longer-term opportunities, the concern amongst many in the industry is that the almost instantaneous change in the trading relationship with the EU would exert severe pressure on just-in-time supply chains at a time when storage capacity will be already limited in the lead-up to the busy Christmas period.

Impact of a No-Deal Brexit on Farm Profitability

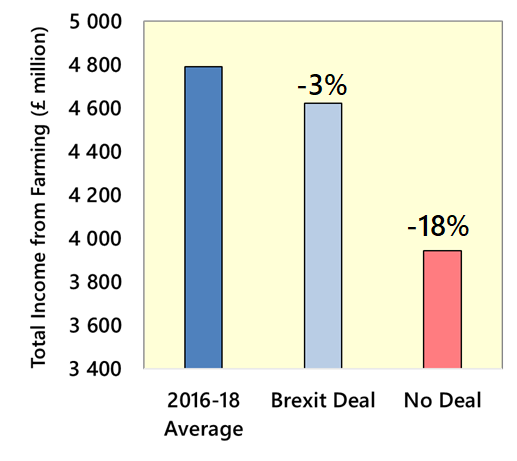

With the UK due to leave the EU on 31st October and the possibility of a No-Deal Brexit becoming more likely, The Andersons Centre (Andersons) recently conducted research on behalf of the BBC to assess its potential impact on the profitability of UK farming, 9-12 months after Brexit taking place.

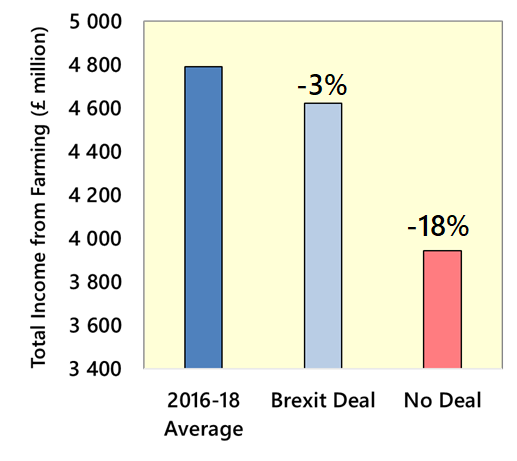

To undertake this analysis, Total Income from Farming (or TIFF) is a useful measure to look at the farming industry as a whole. It is an aggregate, so hides differences between sectors and individual businesses, but provides a simple measure of the profit of ‘UK Agriculture Plc’. In technical terms, TIFF shows the aggregated return to all the farmers in UK agriculture and horticulture for their management, labour and their own capital in their businesses. To allow for yearly variations in weather conditions, markets and exchange rates for example, a three-year average (2016 to 2018) was used as the basis for comparison.

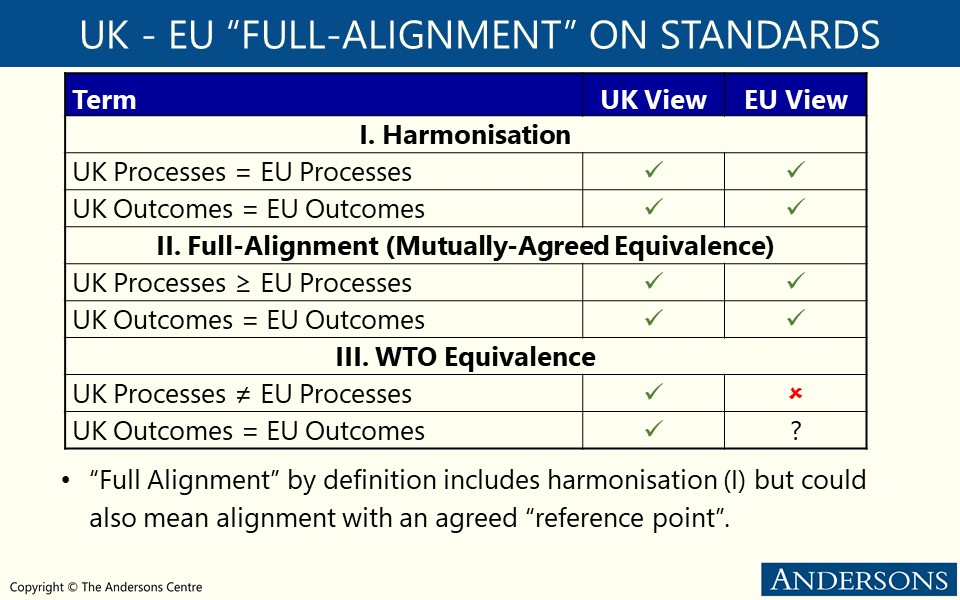

Taking into account previous studies a top-level assessment of the impact of both a Brexit Deal and a No-Deal on the output of each farming sector was compiled in addition to an estimation of the effects of both Brexit scenarios on key costs which are incurred by UK farming. This assessment considered the potential impact of tariffs (including the UK’s March 2019 announcement on its No-Deal Brexit tariff schedule), non-tariff barriers and tariff rate quotas. Importantly, it was assumed that support levels to UK farming were kept constant as the UK Government has committed to farming receiving current levels of support until the end of this Parliament (scheduled to be 2022).

Under a Brexit Deal scenario, a small decline in profitability (3%) is projected; however, under a No-Deal, an 18% decline is forecast.

Impact of Brexit on UK Farm Profitability under a Deal and No-Deal Scenario

Sources: The Andersons Centre

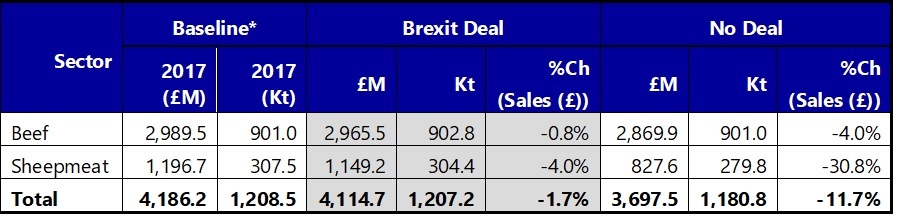

Like all top-level industry averages, there is significant variation within the overall estimate. For instance, where output is concerned, substantial declines are forecast for sheepmeat (-31%), whilst output for cereals, milk and beef production are also down. Some increases are projected for horticulture and intensive livestock (pigs and poultry) provided there is sufficient labour available for undertaking operations.

With respect to costs, some decreases are forecast for inputs which would be affected by the introduction of lower UK import tariffs under a No-Deal scenario. Examples here include animal feed, fertiliser and plant protection products. However, other inputs such as veterinary costs are projected to rise as it is anticipated that there would be a significant increase in demand for veterinary staff to assist with border inspection operations.

An 18% decline in profitability would equate to a hit to UK farming generally of almost £850 million. With many farms already struggling to break-even, the viability of many farming businesses will be in jeopardy. Unsurprisingly, grazing livestock farms (particularly sheep) would be the most exposed given the output declines mentioned above, but a No-Deal would also result in a significant downturn for dairy farming in Northern Ireland, given its reliance on having its milk processed in the Republic of Ireland.

For further information on how a No-Deal Brexit could affect farming and to address the trade-related risks arising, Andersons is running a webinar on Thursday, 12th September to provide further information on how businesses can prepare. Further information is available via:

https://attendee.gototraining.com/r/1384475755831393282

30 Days to Find Backstop Alternative

Despite its intransigence for much of the summer on renegotiating the Withdrawal Agreement (including the Backstop), the German Chancellor gave some hope to the Prime Minister when she suggested, on 21st August, to give the UK Government 30 days to come up with an alternative arrangement which is legally operable and would not result in infrastructure along the Irish border. However, the EU was adamant that this did not mean that the entire Withdrawal Agreement could be negotiated which some in the UK have been seeking.

This additional flexibility from the EU is a welcome development as it is clear that the only way to resolve the outstanding issues is to at least have the opportunity to talk about them. The EU’s previous stance of seeing the Withdrawal Agreement as being completely closed and not up for any discussion was unhelpful and was ramping up the possibility of a No-Deal Brexit. That said, the EU is not going to budge on the central issue of having a fall-back (Backstop) that would apply unless and until a legally operable alternative to the Backstop would be found.

To date, all of the Alternative Arrangements’ proposals put forward have fallen short of the EU’s requirements. This is because the proposals have either required some form of infrastructure on the Irish border, checks between NI and GB or would undermine the integrity of the EU Single Market in some way. Time will tell whether new ideas will come forward in the next three weeks or so to resolve the impasse or whether some ‘fudged Backstop’ will emerge containing elements of the existing Backstop, the previously proposed ‘NI-only’ Backstop and some additional alternative arrangements.

Opposition Coalescing Around Avoiding a No-Deal

Meanwhile in Westminster, various opposition parties (and some Conservative rebels) have been working more closely together to avoid a No-Deal Brexit on 31st October. Although such discussions previously centred on putting forward a No Confidence motion in the Prime Minister, it now appears that the main focus is on forcing the Government to extend ‘Brexit Day’ beyond 31st October if the alternative would be a No-Deal Brexit. This approach is thought to have the best prospects of getting Conservative rebels onboard as their support would be crucial. The Prime Minister has not ruled out the possibility of proroguing (suspending) Parliament so that it would be unable to vote on such a motion.

Overall, as Brexit reaches its climax something is going to have to give. The Government is intent on exiting on 31st October “come what may” and the opposition is uniting around avoiding a No-Deal Brexit, initially via another extension. Whilst the EU has made some very small concessions, it will not U-turn on its red lines which include the Backstop. Amongst all of this, the possibility of another UK General Election should not be ruled out.

For the UK food and farming industry, whilst the uncertainty continues, every effort should be made to prepare for a No-Deal Brexit because according to most experts, it is more probable now than at any time throughout the Brexit saga thus far.