UK Combinable Crop Harvest – What Should We Expect?

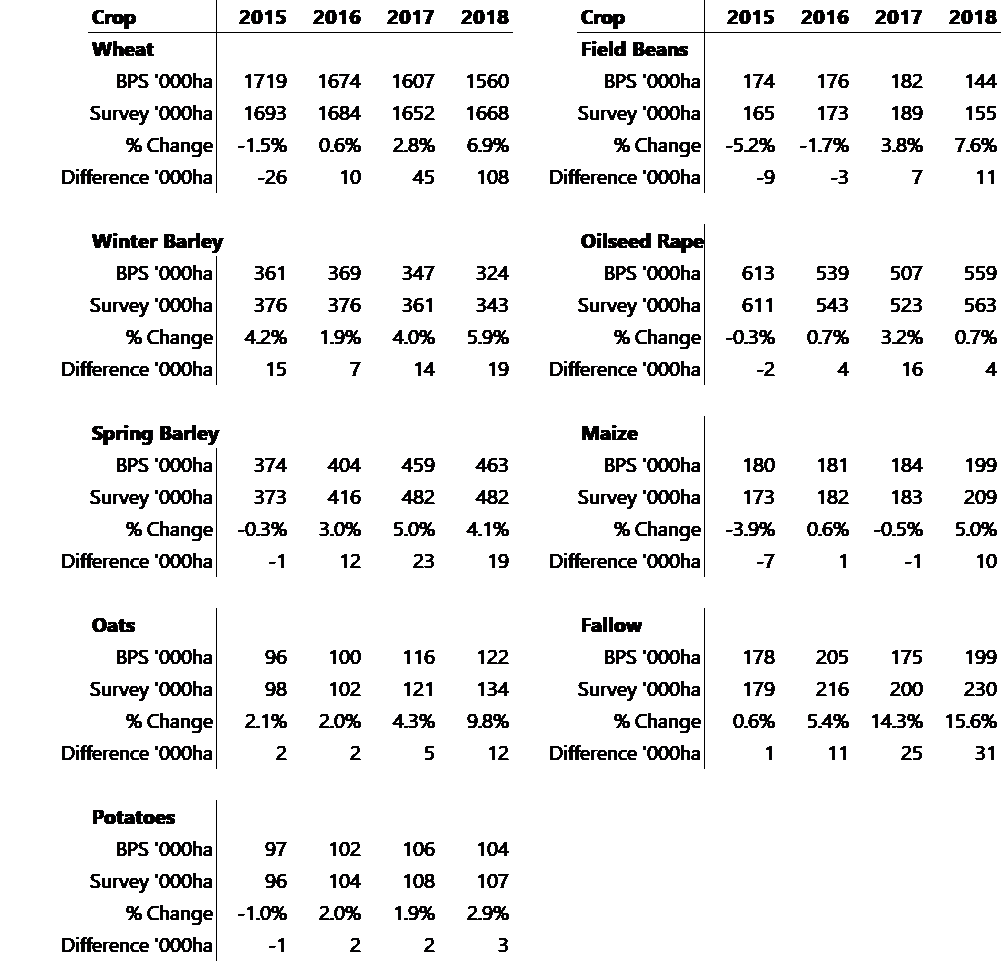

The harvest is in its early stages; it started a little earlier than usual and for some, even earlier than last year. Considerable activity until Thursday last week was seen with barley, oilseed rape and even some wheat reaching the barns, but the storms over the weekend have halted most harvesting. We expect a picture of a stuck combine in Friday’s Farmers Weekly as usual!

For much of the UK though, the crops are in a good condition, especially the cereal combinable crops and early indications suggest good yields (albeit early). The jury is still out for oilseed rape, although, whilst we have heard a lot about crop write offs and poor condition crops, there are still plenty of farmers sitting quietly on what looks like a full field of seeds. It is difficult to tell before the combine has been through. The storm over the weekend has flattened some crops at a very late stage which might cause some harvesting problems.

In much of Europe, particularly, France and Germany, the two main grain producing countries, the recent spells of very high temperatures have apparently taken a toll on the ripening crops. However, the crop tonnages forecast remain comfortably above the very poor yields harvested last year.

OSR

Oilseed rape harvest started before the storm. Following the last couple of very dry days of last week, a few farmers had been harvesting very early in the day or trying to wet the seeds to a level that would be accepted by merchants. To recap, the standard FOSFA contract for oilseed rape is for 9% moisture. Oilseed rape is not accepted at moisture levels above 10% (or you would incur drying charges). You gain 1% in price for every 1% the moisture decreases to 6%. Below that point, it becomes difficult for a crusher to extract oils so is rejected. If you are testing the seed and the moisture levels are heading down towards 6%, advice is to stop harvesting, and restart early in the morning (better than late in the evening because the moisture may have reached the seed rather than just the pod). Wetting oilseed rape is not recommended, as it is often uneven, rather, mix it with some wetter seed to make an average moisture within the tight band.

Cereals

The barley harvest too is under way. It is early days and the better yields are always reported first so we reserve our judgement for a month. Barley harvest in France is a quarter through and moving northwards quickly. The very first wheat crops are starting to be cut now too, but it is too early to make any useful comments about it. More next month.

Globally

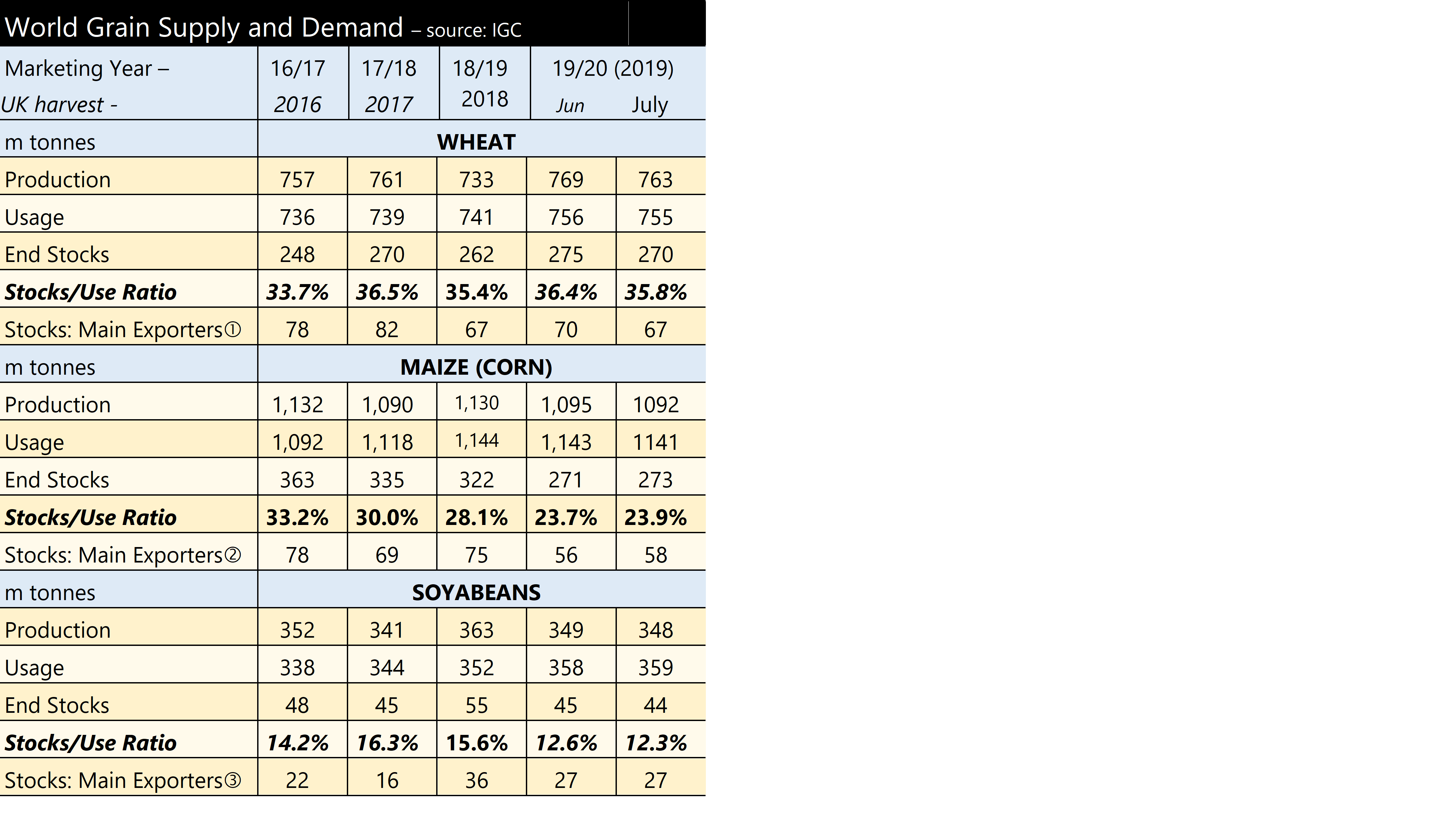

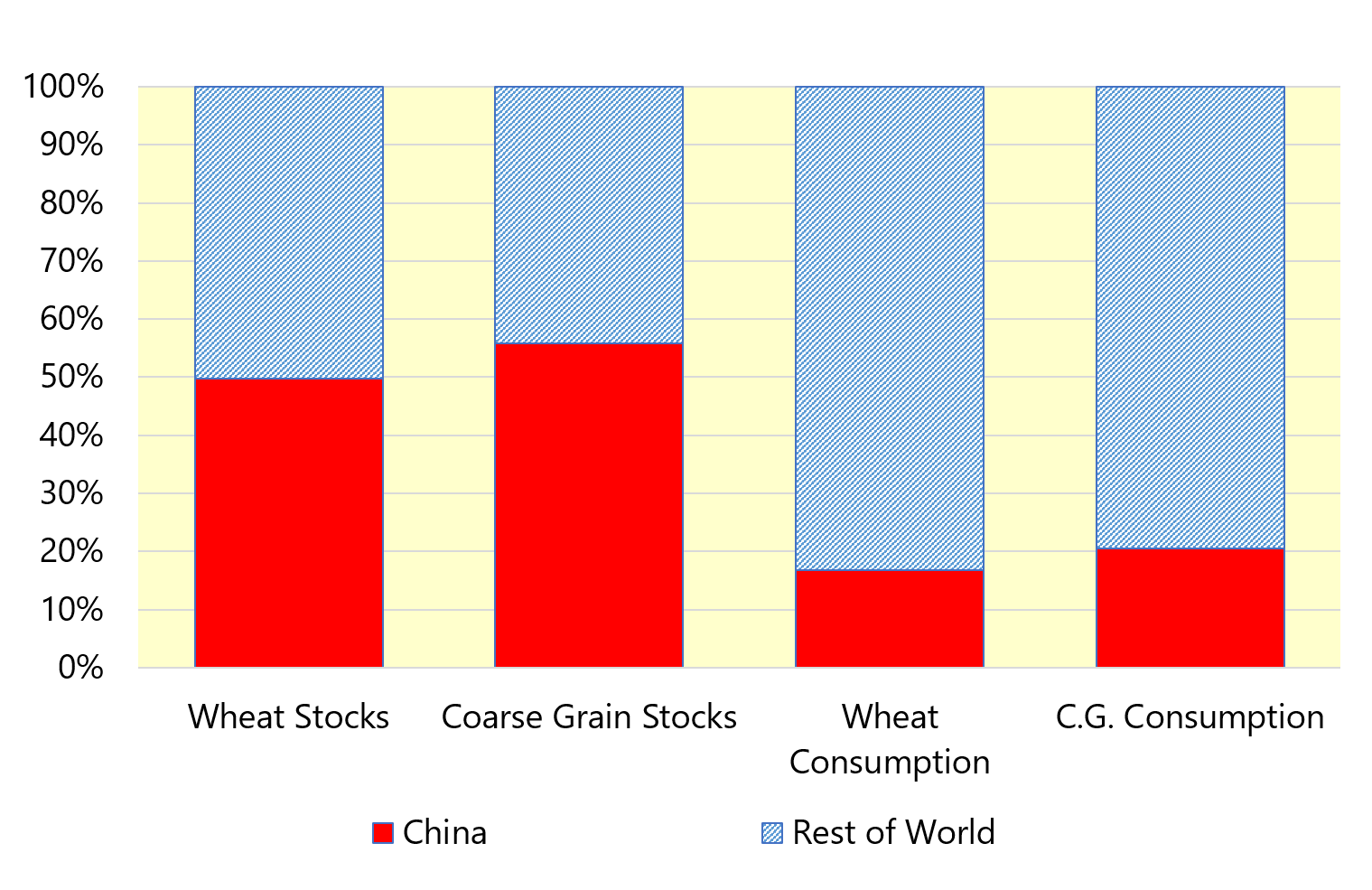

Most combinable cereals are grown in the Northern Hemisphere, so our harvest time will be more or less in line with most others’. Across the EU, harvest is quickly moving northwards, with considerably better results than the poor yields from last year. The Black Sea region and Ukraine are also harvesting, with yields up on last season, although the Russian harvest is smaller than initially projected. North America, the main breadbasket of the grain exporting world is wading through its winter wheat harvest, now being three quarters completed and in China, another large crop is being gathered.

Within a month, the analysts will start publishing their expectations of crop sizes, based not on planted area and trend yields, but more on actual reports coming in from the fields.

This all sounds rather bearish, and often is for a short period, whilst buyers identify what is available, in terms of quality, quantity and location. The calculators then come out and the premiums are established. We note that as the population continues to rise, the overall demand for grains is also increasing every year, and so to simply stand still, the world needs to harvest a record crop each year.

Marketing

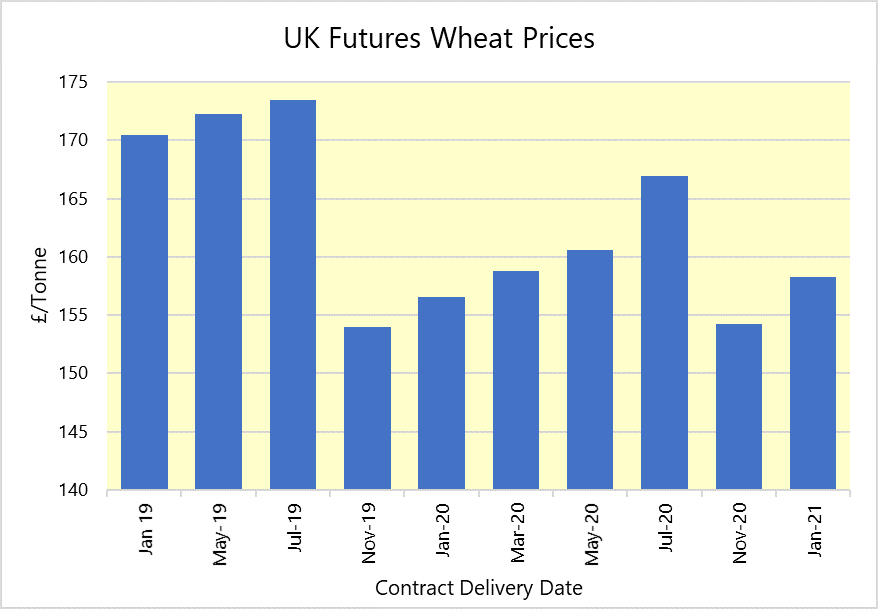

When it comes to marketing our combinable crops this year, we should be more focused on the impacts of a Boris Brexit than the actual marketplace itself. Yes, we acknowledge we made similar comments following last season’s harvest and nothing happened, but there is still a chance that Brexit will actually occur, and more importantly, that it might do so without a deal.

Those with combinable crops to sell are reminded that exporters are not able to book sales to the EU post-Brexit day, because they do not know what the price will be (tariffs or no tariffs), so grain long-holders (farmers) should consider the risks and benefits of holding grain unsold into the autumn. Bear in mind that oilseeds have no tariffs so should not be affected by them, beans have only a low tariff and are mostly exported to non-EU destinations so should be similarly unaffected. However, the cereals are potentially holding a lot of value at the moment because the tariff structure protects them. We will probably have a surplus of feed wheat and oats this year so it might be prudent to pass the risk of these crops elsewhere sooner rather than later (i.e. selling them).