The Wheat Market

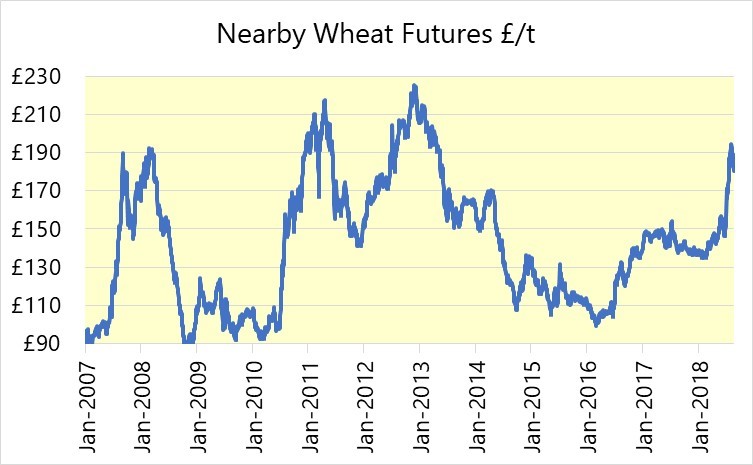

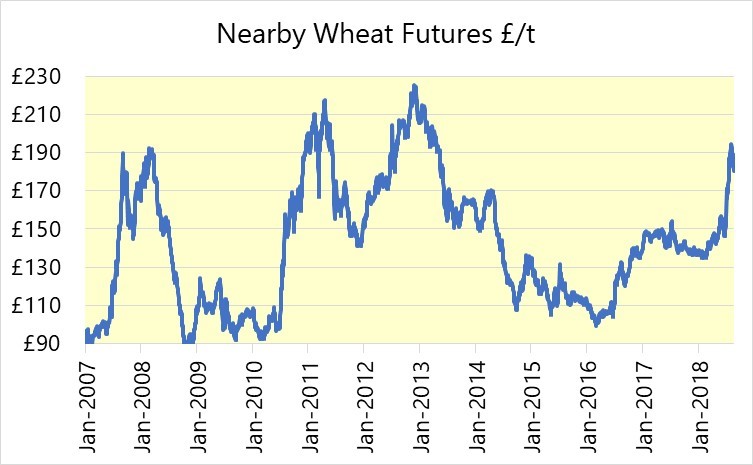

Wheat price this morning (24th August) is a hefty £15 lower than at its high point of the season on the 8th August. It is easy for sellers to become disheartened when they realise that they have missed the best prices. However, only one trade is ever made at the very top of the market, and prices are still very good when looked at with a more long-term perspective. This morning’s wheat price for nearby delivery has only been seen on 6% of the trading days since 2007; that is equivalent to one day out of three weeks. Moreover, prior to this August, today’s nearby wheat price had not been achievable at all for over 5 years, so in fact, maybe it is a great price for sellers. The chart below demonstrates that, since June, prices have risen by £40 per tonne; faster than at any time since the same period in 2010. There are farmers selling grain forward who have never sold grain at this time of the year before and some selling next year’s harvest, before having drilled it. But probably not enough.

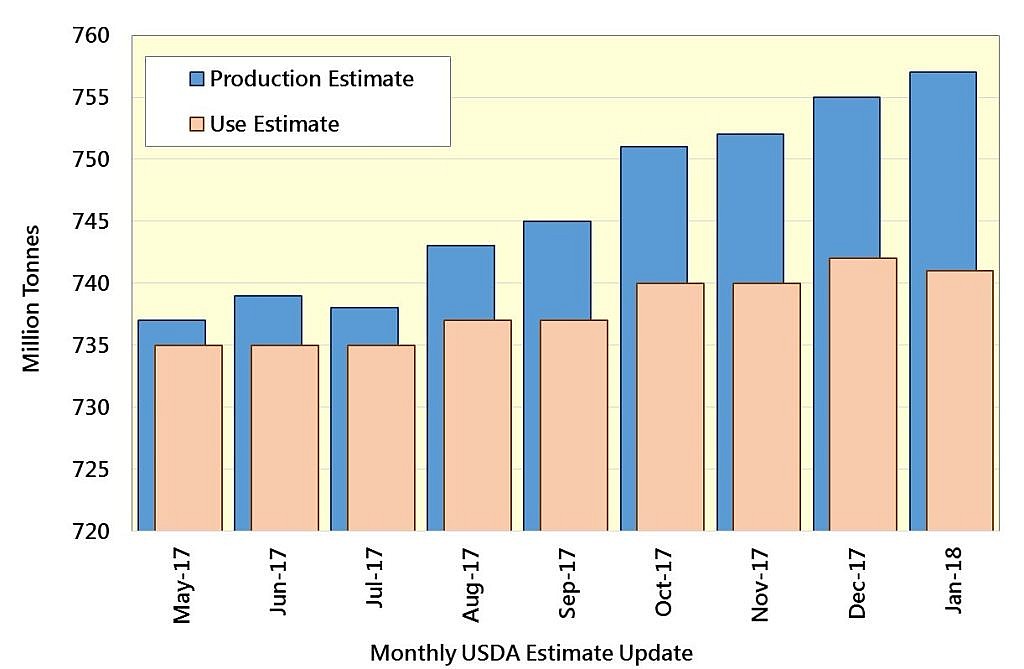

Drought conditions, it transpires, have clearly impacted on crop sizes throughout the EU, Russia, Ukraine and Black Sea countries (for example, Germany is expecting a wheat crop size 23% smaller than last year). There are concerns, largely by Russian grain traders, that the Russian authorities will impose export restrictions to manage domestic supplies; something they have done several times before. Whilst nothing has been imposed yet, there are rumours of export limits of 30 million tonnes. This would be 5 million tonnes lower than USDA export projections for the season, and 12 million lower than last year’s traded volume. Curiously, Russia is likely to have harvested its third largest ever crop this season, but it is still 17 million tonnes less than last year. This demonstrates how Russia has emerged very rapidly as a global agricultural power-house and the largest wheat exporter of 2017/18 and 2018/19. Russian wheat production in 2017 of 85 million tonnes was far more than double their 2012 harvest, and exports were three times higher. This explains why when a Russian official rumours a chance of trade restrictions, the market panics into an opportunity for sellers. Market fundamentals like this are so fickle and unpredictable, the market becomes highly volatile when they are happening, hence the dramatic price fall mentioned in the first sentence. The world is £15 per tonne happier about the availability of the 2019 harvest, than the current crop, in other words prices for next year are £15 per tonne lower at the moment.

Partly on the back of high feed prices, partly as lots of milling wheat varieties were drilled last autumn, and partly as harvest was gathered early, dry, heavy and bold because there was no rain damage this year, there is ample high specification milling wheat. Milling premiums have collapsed to almost 30-year lows of sub £9 per tonne for full specification as a result.

Wheat Yields

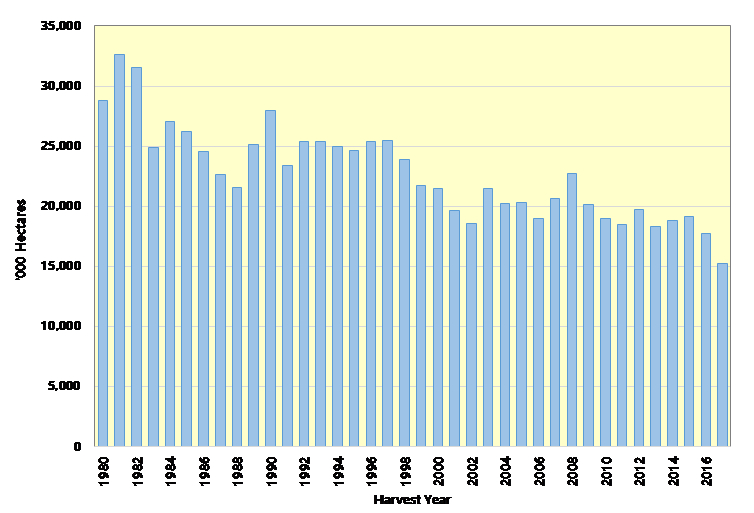

The UK is likely to have harvested a moderate-to-average yielding wheat crop, possibly approaching 8.0 tonnes per hectare, not far from the national average of the last 5 years of 8.2 tonnes per hectare, when field edges and environmental areas etc. are considered. We expect the UK to be a net importer of wheat yet again in 2018-19, making it the third consecutive year and fifth out of the last 7. The UK continues to process more wheat each year, and the area planted is gradually falling, largely of course because of grass weed issues as well as marginal economics unless yields are high and costs low.

UK Wheat Supply & Demand

UK wheat export figures were published last week, confirming the 2017/2018 marketing year (2017 harvest) had the second smallest wheat export figure since winter wheat became the dominant crop in the UK over a generation ago. The other year of such low wheat exports was in 2013, after the dreadful autumn rainfall, preventing many hectares from being drilled. In 2017, the crop size was much more ‘normal’; it is just that it didn’t get sold and therefore exported. Many farmers or traders are therefore still sitting on a considerable tonnage of wheat along the lines of 2.1 million tonnes, which is about 800 thousand tonnes more than is necessary for ‘supply chain continuity’ between harvests. That might well have paid off this year, with domestic feed wheat values now a comfortable £40 per tonne higher than in the spring when the soils were still saturated.

Barley

Barley harvest surprised many people with positive yields and good quality. Initial concerns from some of high screenings have been unfounded and nitrogen levels are usable for most requirements. The UK will have a surplus, and so in the light of concerns of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit, some have considered selling all exportable goods this year.

OSR

The requirement for oilseed rape globally looks set to outstrip production this year, providing support for OSR to gain price lifts above that of the entire grains matrix. However, it should be borne in mind that OSR accounts for only a small minority of vegetable oils output globally. Most oilseed price fluctuation is based on political statements about breaking or resolving trade disputes, the outcomes of which simply cannot be known.

Autumn Drilling

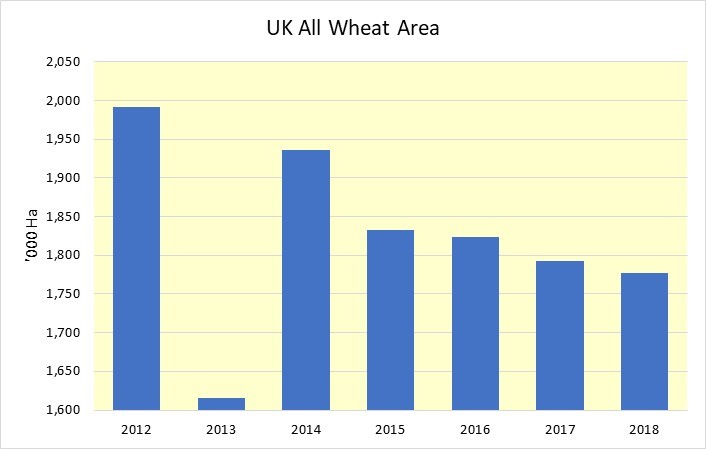

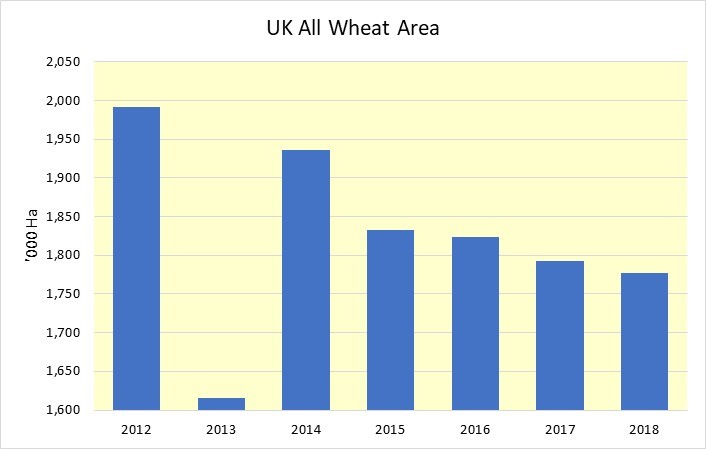

Concerning autumn drilling for 2019 harvest, it is too early yet to provide hard evidence but we expect a continuation of the rise of spring cropping and possible continued experimentation with cover crops. For wheat, the chart demonstrates a continued decline of wheat area since 2012, apart from the dreadful weather year of 2012. Whilst we believe this trend will continue long-term, we would also recognise that a ‘regression to the mean’ (small, 1-year increase) is also entirely possible.