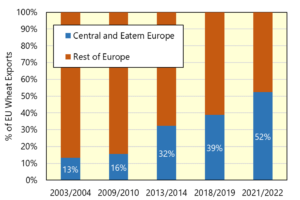

In February’s Bulletin we highlighted that the fast pace of imports of Ukrainian crops into the EU was pressuring prices. This came to a head in April with Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia announcing bans on the import of Ukrainian agricultural goods. The EU has proposed measures to guarantee that crops moving into those nations are re-exported and do not remain in those five domestic markets. In addition, the EU has proposed the provision of €100m to compensate farmers in those nations. At present there is no agreement on whether this deal will be accepted. The news of the bans initially supported prices, but they have subsequently fallen.

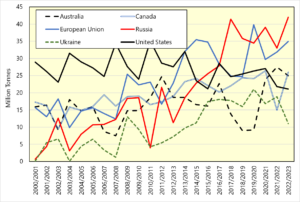

Further uncertainty for grain markets has been caused by the 60-day terms the Black Sea grain corridor now operates under. Comments suggesting the G7 would ban exports to Russia, were reacted to by former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev with suggestions of the Corridor agreement being scrapped in retaliation. This has served to support grain prices in the short-term. Overall, the situation in the Black Sea remains a dominant driver for grain and oilseed markets.

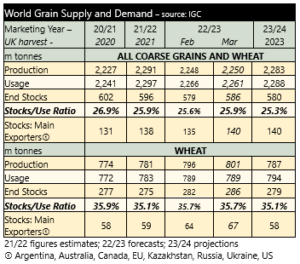

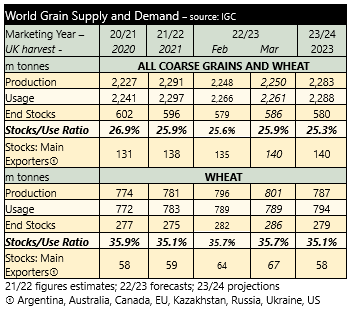

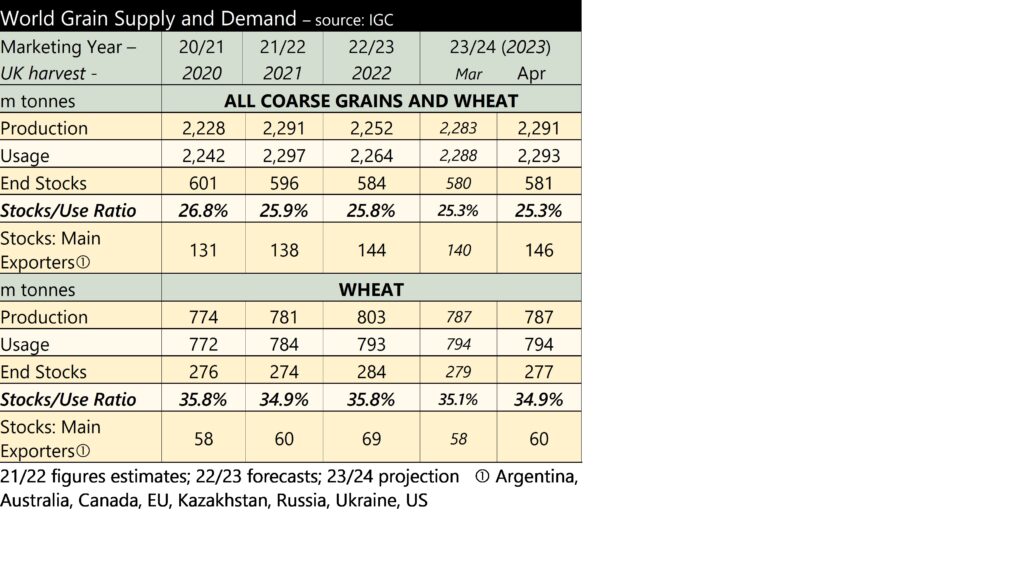

Looking ahead to the global supply and demand picture for next season (2023/24), the global grain stocks picture was eased slightly in the latest International Grains Council supply and demand figures, owing to greater maize production, particularly in the US. That said the overall picture remains tighter year-on-year. With weather concerns in part of the US, particularly for wheat, any adverse weather would support prices.

UK grain prices moved higher following the uncertainty around Black Sea grain movement. UK feed wheat (ex-farm, nearby) was quoted at £190 per tonne in the week ending 21st April. This is up around £8 per tonne on the month. The milling premium also extended slightly, quoted at £61 per tonne. Feed barley has struggled to find demand in 2023 but has been able to compete into export markets recently. The feed barley price was quoted at £170 per tonne, on 21st April.

Oilseed rape prices have fallen since the start of the year. However, concerns around dry weather in Argentina has continued to cut soyabean production forecasts supporting the wider oilseed complex. Oilseed rape prices have risen by nearly £30 per tonne, month-on-month, to £380 per tonne. That said, expectations remain for bigger global rapeseed crops in 2023/24. Also, a bumper Brazilian soyabean harvest is expected which adds pressure vegetable oil markets. Oilseed rape prices may be supported in the longer term with the EU Parliament backing a ban on imports linked to deforestation, including palm oil and soya. Companies selling into the EU will now have to provide verifiable information that goods were not grown on land which has been deforested after 2020.

Pulse prices have been stable month-on-month, with pea and bean prices unchanged at £226 and £220 per tonne, respectively.

The last month has been a busy one for the majority of arable farmers, the wet conditions of March have led to a backlog of planting and spraying. While April conditions have not been ideal they have at least allowed field work to continue.