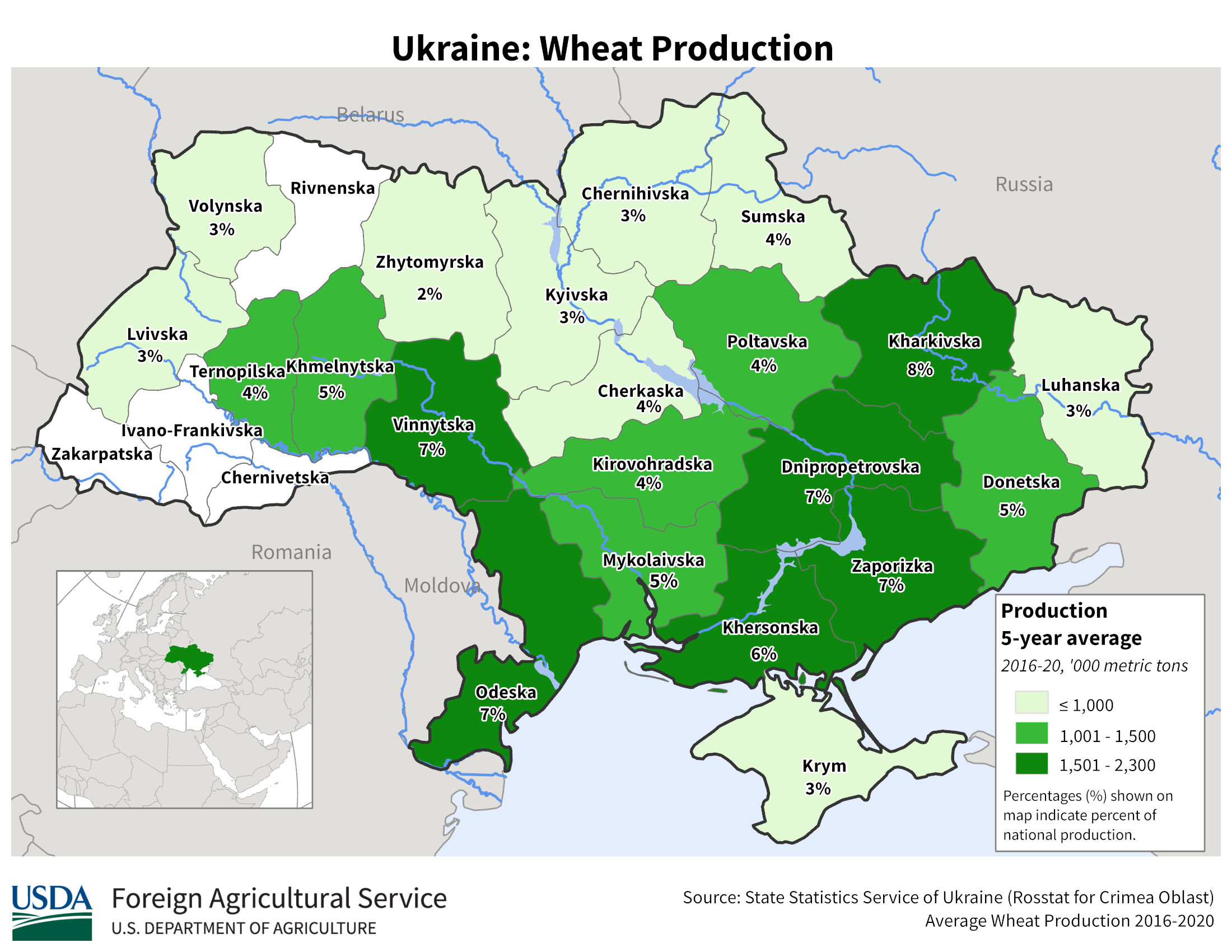

A week is a long time in politics, and given their intertwined nature at present, so too in grain markets. As the war in Ukraine enters into its second month, the impact on grain and oilseed markets has been considerable. This is not surprising when we consider the reliance the world has on both Ukraine and Russia for grain and oilseed supplies.

A week is a long time in politics, and given their intertwined nature at present, so too in grain markets. As the war in Ukraine enters into its second month, the impact on grain and oilseed markets has been considerable. This is not surprising when we consider the reliance the world has on both Ukraine and Russia for grain and oilseed supplies.

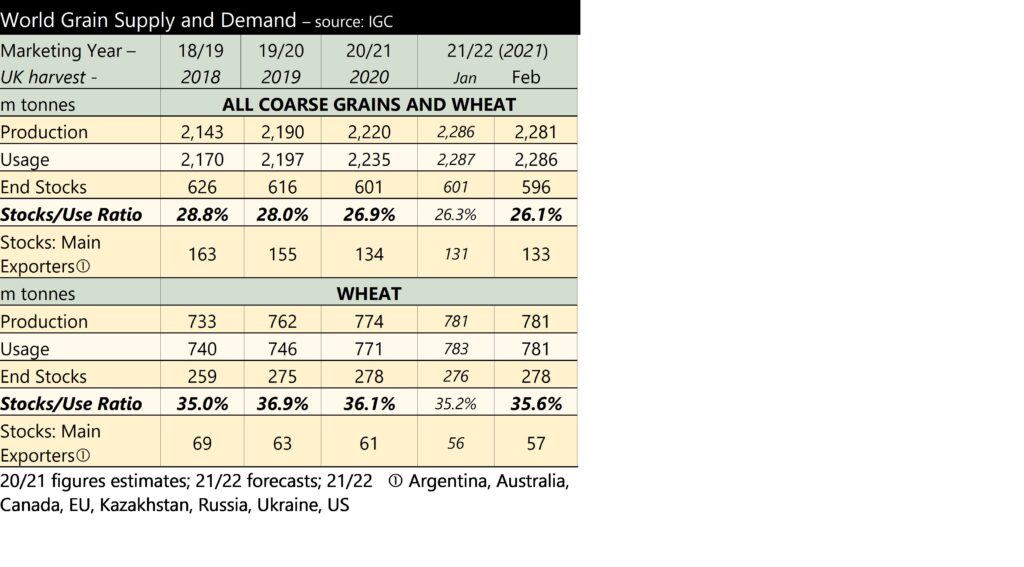

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations held an extraordinary general meeting earlier in March, to discuss the challenge of the war in Ukraine. The report from the meeting highlights 26 countries which rely on Russia and the Ukraine for more than 50% of their wheat imports. Some of those nations will be relatively small importers. However, it is worth noting Egypt, which imports more than 15 million tonnes of wheat annually. Historically, 70% of Egypt’s wheat imports have been sourced from the Black Sea. Whilst we can expect markets to be volatile long after the end of the war, much will depend on how the nations who rely so heavily on Russia align themselves politically going forward.

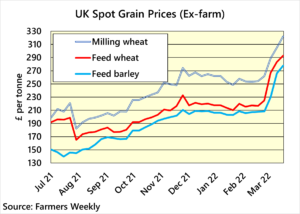

Farmgate grain prices have risen considerably over the course of the last month. Nearby farmgate feed wheat was worth £292.90 per tonne on 18th March, up £69.40 per tonne from 25th February. The value of farmgate prices has been driven by futures market volatility. This is, in turn, making markets challenging to price. Milling wheat prices have also seen increases, although the premiums over feed wheat have remained relatively stable. Feed barley values have also increased considerably, following the direction of wheat markets. Farmgate feed barley increased £67.90 per tonne from 25th February, up to £277.80 per tonne on 18th March.

Outside of the conflict in Ukraine, the grain market would likely be seeing support anyway. Dry conditions over winter in the EU and US, will cause some concern on wheat markets. Drought conditions are also seen in North Africa, if this persists, we can expect increased import demand globally.

Oilseeds prices have also risen considerably in recent weeks. Paris rapeseed futures (May-22) traded at more than €1,000 per tonne on 23rd March. As with grains, there is a global reliance on the Black Sea for rapeseed and sunflower oil. Ex-farm UK oilseed rape prices were quoted at £742.50 per tonne on 18th March.

Pulse prices have also gained over the last month. However, the gain in the value of pulses has been limited compared to that in grains and oilseeds.